On September 26th, 2014, 43 students from the Ayotzinapa Normal teacher-training school, a rural teachers’ college in the Mexican state of Guerrero with a long history of leftist activism and educational empowerment of the surrounding campesino communities, were kidnapped. While en route to protest education reforms and advocate for more school resources in the city of Iguala, the students were caught in open fire by police, arrested, and given to the regional narco-trafficking cartel, Guerreros Unidos. Since then, they have been missing, and while several mass graves in the area have been found, none of them have confirmed to be the missing students.

This senseless violence initiated by the blurred mix of government authorities and narcotraficantes, or drug traffickers, is not new. Since the US-backed militarization of the drug war in Mexico during Felipe Calderón’s administration, Mexico has seen over seventy thousand civilian deaths and twenty-seven thousand more have disappeared. However, in this case, the disappearance of these students, most of who were between the ages of 17 and 23, has fueled almost-daily protests throughout the states. Protestors in the capital city Guerrero set both the governor’s and president’s — Enrique Peña Nieto — palaces on fire. Chants that voice the quotidian anger, mistrust, and grief that have been echoing throughout Mexico: “Fue el estado. Ya me cansé, Todos somos Ayotzinapa.” It was the state. I’m tired. We are all Ayotzinapa.

The relentless global protests that have unfolded in the weeks since the students’ disappearance have created a forceful mill of discontented resistance to the status quo. But a surge of art as both a memorial to the missing and a protest against the government has allowed its creators to speak through these memorials, voicing the everyday frustrations, fears and resistance to the larger political climate that they live in.

The protest artwork that has come out of these events is, much like the protests themselves, meant to be broadcast and consumed widely — the voices of the artists are uniform yet individual, each one echoes national exhaustion and frustration. But the forums that broadcast this message differ greatly. For artists like Yescka, a street artist from Oaxaca and the founder of the political art collective ASARO, the disappearance demarcates a new mistrust of the government. He alludes to this in one of his most recent works, a wheat paste piece of five men standing with their backs against a wall, hands tied, heads down. Three of them have soccer jerseys with the words “Justice,” “Ayotzinapa,” and “October 2nd” written across their backs — an allusion to the 1968 Tlaltelolco Massacre when military and police killed some 300 students in the Tlaltelolco sector of Mexico City — one of the major events that fomented deeply rooted public doubt in the national government.

Much of the violence that has been wrought on civilians in Mexico has been directed at indigenous and rural farming communities — the events at Iguala are no exception. The innocence and impoverishment of these victims has also propelled the anger behind recent protest. As the father of one of the missing students put it, “The authorities…have done the very worse that you can do, to the most humble of people.” Recent artwork pieces, which stem from frustration over longstanding institutionalized violence towards these communities, have given visibility and power to the concerns of the indigenous and farmer populations in Mexico in the protests and the nation’s long history of racialized violence. Photographs on La Jornada de Solidaridad, an online collection of artwork protests against Ayotzinapa, reference the Zapatista movement in Chiapas—a leftist indigenous-led political and military movement based on indigenous Mayan beliefs.

Elsewhere, the protest artwork that has brought visibility to the rural farming and indigenous communities has been student-led — blending cultural aspects of the protests with resistance against Mexico’s longstanding track record of violence against students. Outside the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico’s Palace of Fine Arts, students from the Escuela Normal Rural de Ayotzinapa and El Centro de Educación Regional de Iguala have protested through regional dances and painted portraits of the missing 43 students. Dancers carried photographs of the students as they danced around the plaza in front of the palace, encircled by musicians who had pasted protest slogans on their backs of their guitars.

Despite the government’s historical desire to close down many of the normal teaching schools that train young people from rural communities to teach, these artistic performances that took place in the symbolic and literal heart of the federal government served as a reminder that the schools and their students were still thriving. The dances, songs and the sheer number of students symbolized that the cultural past of Guerrero and the social future of their communities would not be suppressed even in the midst of so much state violence. But the ghostly faces of the 43 missing students that danced around on their bags, signaled that they would not forget those who were lost, gone or missing.

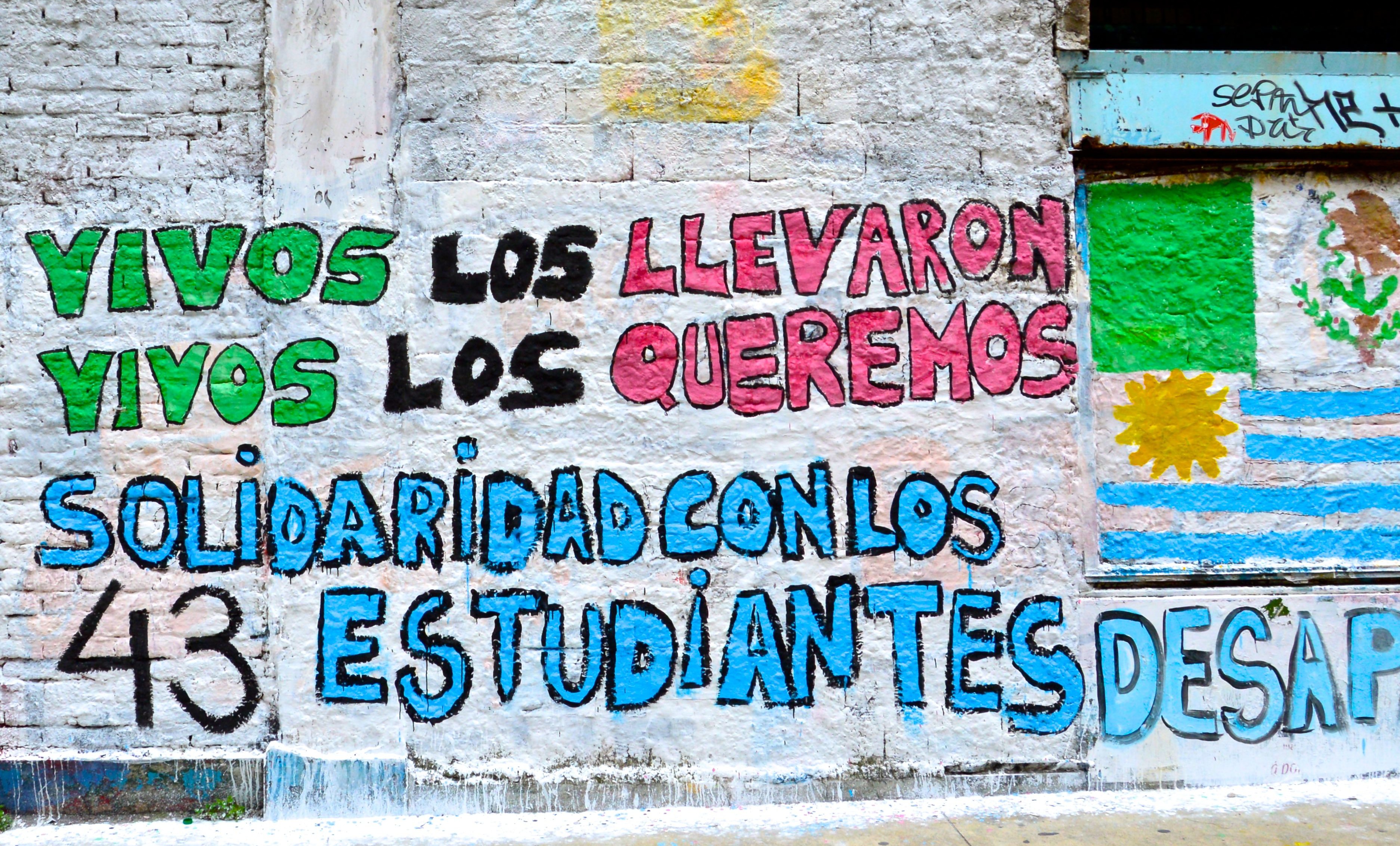

Beyond the state borders of Guerrero, Mexican citizens have stood in solidarity with the families of the missing students by staging protests in every major city in Mexico and encouraging workers and students to refrain from working and attending school in an effort to stage a national strike. The protests have reached cities as far as Holland and Barcelona, where protestors drew life-size cardboard silhouettes of each other and painted the names of the missing on them, echoing the chant: Ayotzinapa somos todos, we are all Ayotzinapa. Though it is unclear how long the protests will continue or whether or not they will be followed by harsh state retaliation, what has become clear is that the movement it has created will not be easily forgotten. The outcry of protestors has gone beyond the echoes of chants in the streets; it has become a swell of artwork that spans state and national borders, that is literally pasted to the walls, that allows individual grief and outrage to be voiced through thousands of hand-drawn pictures of the missing on the internet. “Perdamos el miedo, alcemos la voz.” Loose the fear, raise your voice. The protestors of Ayotzinapa have raised their voices through this art, and they will not be shutdown easily.