Mass incarceration has found a comfortable home in the underbelly of American life. It slips through the cracks of democratic oversight and represents one of the more lucrative public-private partnerships of our time. In recent years, a vast trove of literature has shed light on this country’s tendency to isolate its most vulnerable citizens from free society. Works like Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness have made waves, bringing the plight of the incarcerated into mainstream conversation. Sentencing laws, drug decriminalization and police brutality are topics of extensive public discourse, but the barriers released prisoners face when it comes to health care is a subject that is less well understood. Reentering society after a period of incarceration is physically and emotionally taxing. Former prisoners face stigma, poverty, a loss of social networks and the inability to navigate what meager resources are available to them. But worst of all, the 1,885 people who leave prisons in America every day face very tangible barriers to health — barriers that policymakers and health professionals are only beginning to understand.

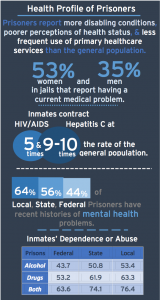

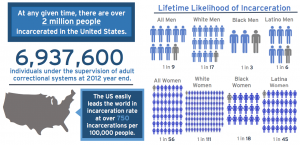

American prisons disproportionately house the poor and people of color: 1 in 3 black men will be imprisoned over the course of their lifetime as will 1 in 6 Latino men (1 in 17 white men will face the same fate). These two groups are incidentally also at the highest risk for being uninsured. Since the Affordable Care Act, the uninsured rate for blacks has dropped by 13.8 percentage points; while that of whites sits at 9 percent, and Latinos, at 33.2 percent, still have the highest uninsured rate. Despite the inherent risks of lacking insurance, the incarcerated have a higher burden of infectious disease, substance abuse and mental health issues than the general population. Anywhere between 64 (local jail) and 45 percent (federal prison) of prisoners have “symptoms of serious mental illness,” as opposed to 20 percent of the general American population. Furthermore, 65 percent of all inmates meet the criteria for substance abuse problems. Because mental health and substance abuse issues are rarely adequately addressed in prison — only 11 percent of incarcerated addicts receive adequate treatment —inmates are in particularly high need of medical attention upon their release. Yet, more often than not they exit prison uninformed and uninsured with no support network to turn to.

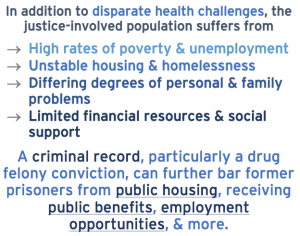

One of the more pervasive challenges faced by individuals post-release is access to consistent health care, in part because this is one of the major challenges they faced prior to entering the correctional system. Indeed, drug crimes related to addiction and preventable crimes caused by chronic mental health issues are the underlying origins of incarceration in many cases. Indeed, “failure to treat addiction and mental illness as medical conditions… often leads to behaviors that result in incarceration.” Consequently, releasing prisoners back into society without providing accessible preventative care arguably plays an important role in re-incarceration.

While the Affordable Care Act extended insurance coverage to single male adults who may not have qualified for Medicaid prior to 2014, many incarcerated individuals will continue to be ineligible for health coverage in states that are not expanding their Medicaid programs. While these individuals will need contact with health professionals immediately upon release from prison, their lack of insurance coverage in many states will make it impossible for them to seek necessary treatment in the community. According to mortality statistics for recently released inmates, the risk of death in the first two weeks after release from a correctional facility is 12.7 times the average risk of dying for the general population. Lacking health coverage only exacerbates the difficulties of successful reintegration.

The picture for the vulnerable and incarcerated is grim. Even in Rhode Island, which is in the process of implementing Medicaid expansion to all adults, the incarcerated face a plethora of social challenges upon release from prison. According to Bradley Brockmann, executive director of the Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights in Providence, the poor health status of prisoners is only a symptom of the larger problems facing the United States today: “The three largest psychiatric facilities in the country are the New York, Chicago and Los Angeles jails.” Brockmann asserts that treatment in the community for substance abuse and mental health is essential to stop prisoners from cycling in and out of American jails. But he also acknowledges that society and the medical community are not yet prepared to deal with substance abuse and mental health in the same way as physical health. While Rhode Island is taking steps to sign inmates up for Medicaid so that they will be insured upon release into the community, Brockmann remains skeptical, “Getting prisoners their Medicaid cards is a huge first step. [But] successfully connecting prisoners with the healthcare system has to be understood and addressed within a whole spectrum of competing re-entry needs.”

Although many state and nongovernmental entities are working to help people who have passed through the correctional system, few resources exist to provide comprehensive social services for the previously incarcerated. Indeed, the particular composition of the corrections-involved population means that programs must combine medical and psychiatric treatment, rehabilitation for substance abuse, residential components and comprehensive case management. Project Bridge, a Rhode Island-based effort to link HIV-positive inmates with high-quality care post-release is one innovative approach to addressing the pressing health needs of inmates.

Transitions Clinics are another approach developed to link chronically ill patients with medical care provided by community physicians trained in correctional health. The centers are also unique in that formerly incarcerated community health workers conduct case management as well as in that the Clinics are located in communities with high incarceration rates. The aim of Transitions Clinics is not just to improve health and well being, but also to reduce the chance that individuals will return to the correctional system. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics data compiled across 30 states, two-thirds of inmates released from state prisons are arrested for new crimes within three years of returning to their communities. “Transition Clinics is probably the best model that we have right now [in terms of reducing this vicious cycle],” says Brockmann.

Until now, recently released inmates have been told that surviving outside prison walls is a product of their attitude and willingness to succeed. But individualistic rhetoric is a double-edged sword. Indeed, people in prison or returning to their community may need the kind of hope, encouragement and sense of independence this ideal provides. However, it is crucial that policies pertaining to the incarcerated address the very grave socioeconomic issues plaguing poor and inner-city communities nationwide — issues that are well beyond individual control. Long-term unemployment, ill health, lacking infrastructure and abysmal education are the precursors to incarceration. As the incarcerated leave prisons, they return to the same fruitless economic deserts from whence they came. They go home to communities that are poorly equipped to handle severe mental illness and to a health care system that has not developed effective practices for dealing with addiction as a disease rather than a crime. According to Brockmann “people are finally getting the [coverage] that they should’ve been getting — but we still have the challenge of dealing with people with criminal records who can’t get jobs; seeking healthcare becomes a low priority.” Leaving prison should be a happy time — a time of freedom and homecoming. But for the millions who pass through American correctional facilities annually, freedom isn’t free enough. As for the future, Brockmann says, “What is key now is… finding solutions to address non-health needs in a health arena. There’s nothing really innovative going on because we’re still at a point of dealing with these really intractable problems.”

Great article