Since the founding of America, religion has always been both a powerful influence and a blunt weapon in political discourse. Politicians from across the aisle have no qualms in bringing up their religion when debating policy and passing legislation. As it is across most of the West, Christianity tends to be the religion most represented in the halls of government. No stranger to controversy, Catholicism has grown from a highly persecuted religion to one of the most powerful and influential of the Christian denominations in America. The largest and one of the oldest religious institutions in the world, the Catholic Church has often found itself allied with conservative national factions, which, in the case of America, would be the Republican party. Not all is clear-cut in religious politics, as complex issues continue to arise as divisions between the Church hierarchy and the American political establishment.

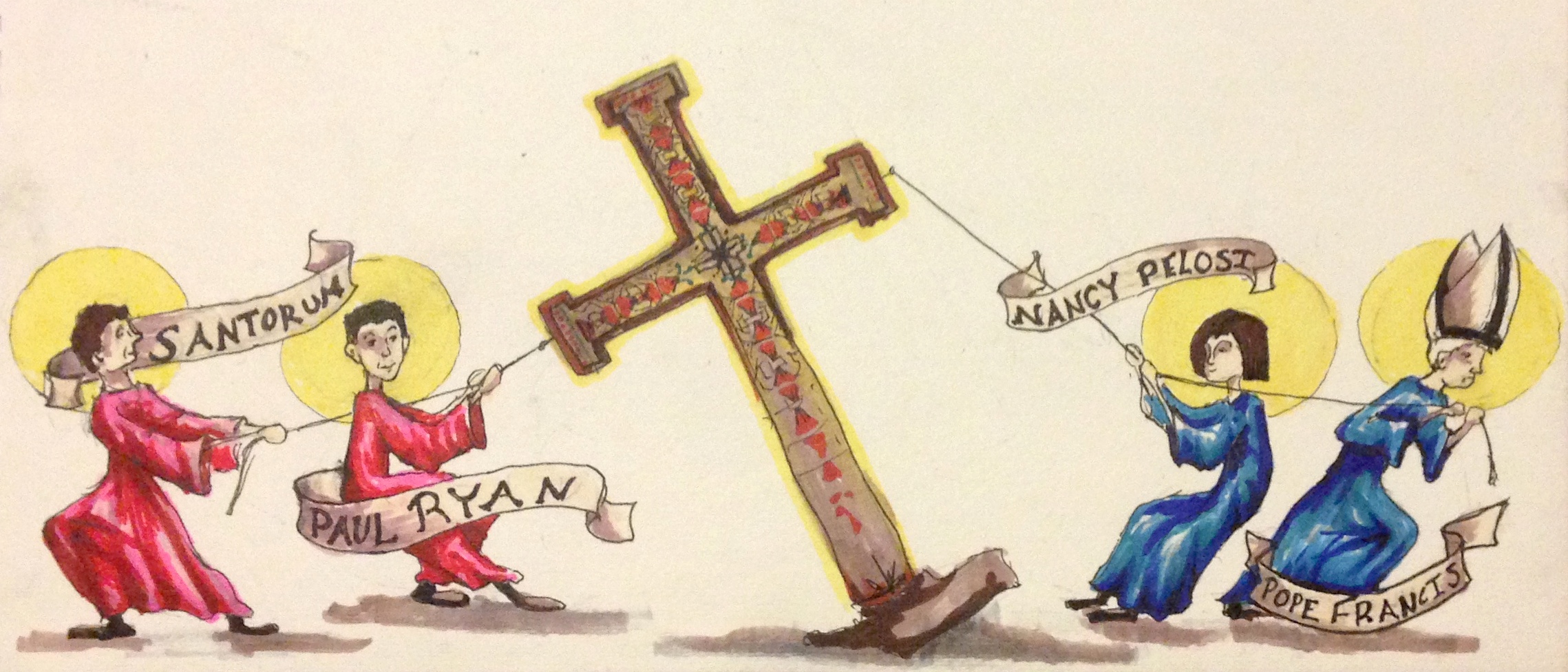

Republican Catholics have been known to frequently invoke their religion as they discuss policy, and above all, have always found a safe refuge in the halls of the Church when debating abortion and gay rights. There is a precedent of clerical objection towards contraception and abortifacients in the Church dating back to its early days. This has created a long-standing opposition to abortion and contraception that is largely institutionalized. In countries with a contemporary history is not defined by more stringent secularization and whose majorities are comprised of Catholics (for the most part, Catholic nations outside of Western Europe), abortion is illegal under most circumstances. Ireland, Brazil, Poland, Argentina and the Philippines all ban abortion in all but the most exceptional of circumstances, often to dramatic and shocking effect. Meanwhile, in American Catholic dialogue, scripture is thrown into the ring of public debate like no other, with politicians and prominent figures across the aisle lapsing into evangelization and accusations of heresy. As such, at times Catholics of all stripes have lapsed into more extreme discourse, although the Church rarely, if ever, crosses such vociferous liturgical boundaries of speech.

Some issues are more clear-cut in scripture and the religious establishment than others, and this varying complexity affects the ease with which some Catholics integrate conservatism and Catholicism. A long exegesis on the Biblical discussion of immigration policy is a lot harder to put on a Fox News segment than a simple citation of Leviticus 18:22, “Do not have sexual relations with a man as one does with a woman.” The simplicity of the argument against homosexuality as told in scripture is a lot easier to explain than the convoluted and complex arguments and guidelines on immigration. Many of the party platforms and ideological pillars that form much of contemporary Republicanism are compatible in part with conservative Catholicism. Therefore, it is easy for orthodox Catholics to fit into the Republican system.

Though the Catholic Church dovetails well with conventional Republican beliefs on the subjects of abortion and marriage equality, the two have a quite substantial split on the subject of immigration. While respecting the legal rights and judicial necessities of maintaining a secure border, the Catholic hierarchy spares no detail in telling the United States that most, if not all, undocumented immigrants deserve citizenship. It may come as a shock to many that the largest Christian denomination in the United States has been a longtime foe of the Republican Party on the topic of immigration reform. With a long and storied history of supporting immigrants in the United States dating back to early waves of Irish and Italian immigrants at Ellis Island, American Catholicism has deep and recent roots in immigration. Pope Francis, as well as the Council of American Bishops, is an open supporter of such reform in the United States, and even successfully appealed to President Obama himself in the case of one young girl whose father was about to be deported. Even the catechism of the Church — the text in which the Church’s tenets and teachings are described in detail — states that “prosperous nations are obliged, to the extent they are able, to welcome the foreigner in search of the security and the means of livelihood which he cannot find in his country of origin.”

Religious diatribe is not often found in right-wing arguments against immigration reform. Fervent, race-tinged nationalism is much more common. The idea of a unified, English-speaking America with a European heritage may not be explicitly related, but the speech of even moderate anti-immigrant Catholic politicians tacitly references a similar idea. One Catholic politician, David Schweikert, even advocated for removing birthright as a way of getting citizenship. It was not long ago, however, that there was a huge outcry and prejudice against Catholics themselves; something that few Republican Catholics seem to acknowledge about their heritage. If it were not for birthright laws, the possibilities of mass deportations for European Catholics would have been high. Lamentations of the lazy worker from south of the border taking American jobs abound in conservative talk radio, and are pedaled heavily by Catholic Republicans. The supposed economic consequences (many proven false) of illegal immigration also constitute a common argument among opponents of immigration reform. The nature of this particular argument is notable for its incongruities with debate on social issues: Catholic politicians rarely cite any economic benefits or consequences of either abortion or gay marriage, and do not recognize any sort of oppression against members of the LGBTQ community as akin to the oppression many Catholics faced for most of America’s history. Republican Catholics’ selection of topics in which to invoke religion seems inconsistent at best.

Catholic politicians break away from the Church on certain hot-button issues as a result of both political exigency and the tension between Catholic catechism and conservative canon. The Church doesn’t endeavor to have strong positions on some subjects, and immigration and healthcare are perhaps two such topics. Religious organizations, and more relevantly, the Church, only offer guidelines on healthcare policy and immigration (although they tend to be critical of both, given that healthcare policy is relatively liberal, and immigration policy is relatively conservative). These are complicated issues that do not fall along partisan lines. For that reason, Republican politicians often find it difficult to reconcile with the Church’s position on issues that are not politically convenient positions.

Such fractures in the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Republican Party have further cracked as Church has continued to defy its supposed rightwing reputation and conservative public image. In a powerful protest of immigration laws, a group of cardinals and bishops held a mass at the border with Mexico. Passing out the Eucharist through the border fence to prospective migrants, they sent a clear signal to the United States government and Catholic politicians that the current system is in dire need of change. High-ranking bishops and cardinals, as well as lower-ranking priests, have little fear of writing scathing editorials decrying the immigration system. Sometimes, clerics implicitly call out politicians in their own congregations. Moreover, Pope Francis, considered quite liberal and populist, has commented heavily on this issue. Speaking on immigration worldwide, he echoed the Church’s catechism, “All have the same right to enjoy the goods of the earth whose destination is universal, as the social doctrine of the Church teaches.” Essentially, all humans deserve equal rights across all borders, something many bishops in the United States and Latin America say the United States is denying undocumented immigrants.

The Church was actually a very ardent supporter of healthcare reform. While always acknowledging the shortcomings in our medical services industry, the Church has advocated for reforms throughout the decades in order to help uninsured and poorer Americans. Only the Affordable Care Act’s provisions on birth control and the furor over abortion funding were against the Church’s teachings, causing the Church to pull support from it and challenge it repeatedly in the federal courts. While portrayed in the media as staunchly against the reform, the Church wholly supports a more socialized healthcare, possibly even inferring that the ACA would not be enough.

As we approach the midterms, both the Church’s influence — and in some cases its lack thereof — must be taken into account. Long used as a tool of the Republican establishment and right wing, the Church has the power to influence the opinions of many of its scattered faithful. American Catholics have long been a potent force, but one notably divided. Never having voted in a bloc, Catholics have no seeming intention to form one now. The Church’s influence, rather than in attempts to sway voters one way or another (which may still yet have an impact), has been found in its grassroots organizational skills and international platform. As written above, the Church is already launching a wide-scale effort pushing for reform, including large and emotional acts and publications that are simply too important to dismiss as mere publicity stunts. With a highly popular and reform-minded pope, more people are likely to listen to what the Church has to say on immigration, potentially starting a dialogue on a key issue in the upcoming election. By framing the immigration in a humanitarian and religious light, the Church can make a substantial contribution to the debate around immigration reform.

Bishops on the Border | Brown Political Review http://t.co/ZaAra7r9vQ