Sri Lanka has long been a matter of contention in Indian domestic and foreign policy, a topic relevant to India’s upcoming general election (April 7th to May 12th). Tension in Sri Lankan-Indian relations reached new heights when Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh decided to boycott the 2014 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) hosted by Sri lanka. The decision to send India’s foreign minister instead sparked heated debate about India’s future foreign policy and its commitment to “global responsibilities” such as democracy and international human rights.

This decision illustrated changes in Indian domestic politics, as regional parties from the Tamil Nadu were surprisingly able to influence foreign policy at the federal level and according to some critics, “endanger the country’s [India’s] regional and strategic security interests – a valid concern bearing in mind India’s highly decentralized democracy coordinated through influential regional parties. The CHOGM episode, in which India chose to comply with regional parties’ desires, as opposed to its traditional national approach of noninterference, offers insight into India’s role as a rising global power and subsequent foreign policy developments.

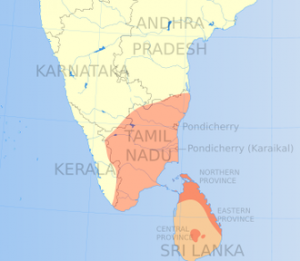

India’s tension with Sri Lanka is rooted primarily in the 25-year civil war between the LTTE – a militant secessionist organization – and the Sinhalese. The LTTE fought on behalf of the Sri Lankan Tamil population for an independent state in northern Sri Lanka referred to as the “Tamil Eelam” (homeland). The Tamils are an ethnic group found predominantly in Sri Lanka and the Indian Tamil Nadu. Ethnic ties with Sri Lanka’s Tamil population therefore influenced and continues to influence India’s policy decisions regarding Sri Lanka.

In 2009, the Sri Lankan government achieved ceasefire at an unwarranted expense of civilian life. The army’s mass-scale violations urged global condemnation forcing India, a nation with ethnic ties to the Tamils and a physical political presence in mediating the 25-year war, into a difficult position. Despite the commonwealth organization’s decision not to hold the 2011 conference in Sri Lanka, in 2013, the nation was named host of the conference and chairman for the next three years, providing the Sri Lankan government an opportunity to repair its international image.

CHOGM, a typically minor summit that attracts minimal attention, became “a media-saturated event.” Although intended to restore Sri Lanka’s global status, the meeting provoked highly charged protests in India’s Tamil Nadu. The belief that Sri Lanka did not intend to address past human rights violations created fertile ground for strong anti-Sri Lankan sentiment. Footage such as a video of the Sri Lankan army killing the ex-LTTE chief’s son merely augmented indignation toward the Sri Lankan government amongst Tamil Nadu activists, politicians and youth groups alike.

In May 2011, Jayalalithaa Jayaram, the previous leader of the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) party was made Chief Minister of the Tamil Nadu. Following the 2011 UN Report of the Secretary-General’s Panel of Experts on Accountability in Sri Lanka, Jayalalithaa released a statement confirming the “human rights violations and brutal repression that was earlier in the realm of speculation or dismissed as biased or partisan reportage.” The fact that the Chief Minister of the Tamil Nadu, a geographically and politically instrumental region within India, had expressed clear opposition to Sri Lanka consolidated the anti-Sri Lankan sentiment and complicated India’s global policy.

As a result of a vocal Tamil Nadu population, India voted for the Report in 2011. Protests in the Tamil Nadu increased exponentially once Sri Lanka was provided the opportunity to host CHOGM. “Boycott CHOGM” became a predominant battle cry in the Tamil Nadu. In an “unprecedented move,” the Tamil Nadu state assembly proposed a resolution urging the Indian federal government to boycott the summit completely. Widespread support for the resolution amongst Tamil Nadu parties reflected a rare moment of bipartisanship between the AIADMK and DMK in Tamil Nadu politics and a strengthening of Tamil Nadu solidarity. The DMK even withdrew from India’s United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in March 2013 due to New Delhi’s refusal to amend that year’s UNHCR resolution against Sri Lanka in a manner that would subject Colombo to an international investigation regarding the 2009 killing of Tamil civilians (the latter a recent amendment to the current 2014 resolution). A year earlier, the head of the DMK revived the Tamil Eelam Supports Organization – the party’s policy instrument most in favor of the LTTE.

Due to the increased power of regional parties, the CHOGM incident caused a polarization within the traditionally non-interventionary ruling United Progressive Alliance. The Minister of External Affairs supported the Prime Minister attending CHOGM to avoid fracturing India-Sri Lanka relations and causing Sri Lanka to lean further toward China. Tamil Nadu voices ultimately prevailed and prevented the Prime Minister’s attendance, indicating the Indian federal government’s loss of autonomy over foreign policy decisions. India’s decision failed to achieve changes in Sri Lanka’s treatment of Tamils and further isolated the Sri Lankan government.

The belief that India’s decision to vote against Sri Lanka was to appease its Tamil Nadu population prior to the approaching election may contradict India’s defense of Colombo in 2009 when the Indian government faced intense pressure from the Tamil Nadu. In both 2012 and 2013, however, India acknowledged the growing autonomy of regional bodies such as the Tamil Nadu and supported two consecutive UNHCR resolutions against Sri Lanka. This decision may also reflect its increasing responsibility as a global power in terms of promoting human rights.

Six days ago, in attempting to strike a balance between domestic and foreign policy, India abstained from the 2014 UNHCR resolution against Sri Lanka. The current resolution proposes harsher demands, calling for an independent international investigation, that according to the Indian Minister of External Affairs, is an “intrusive approach that undermines national sovereignty.” As stated by G Pramod Kumar, a journalist for Firstpost, “now that the Congress has nothing to gain in Tamil Nadu with the DMK deserting it, the party couldn’t care less. The party is not even a contender in the polls in the state with most of its frontline leaders refusing to contest elections. With this vote it also doesn’t lose anything.” DMK’s withdrawal from the UPA therefore may have reduced the party’s desire to appease the Tamil Nadu population, causing Congress to prioritize foreign relations and its larger role in global politics.

India’s temperamental relationship with Sri Lanka has strengthened Sino-Sri Lankan ties, a move detrimental to Indian interests. In 2012 the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hong Lei stated that Sri Lanka should handle the issues raised in the report without external impositions, save support from the international community for the Sri Lankan government’s efforts. In the midst of contentious Chinese-Indian relations, recently concerning border disputes, it is important for India to keep Sri Lanka within its sphere of influence. In light of increasing Chinese interests in Sri Lanka, the Indian federal government is constructing Indian foreign policy architecture conducive to its growing global influence. The CHOGM incident reflects the difficulty of reconciling foreign policy and domestic demands.

If not for the Singhalese…Sri Lanka would be a wealthy, prosperous and peaceful nation, with countries like China needing it more that it needs China…..

If not for tamils Sri lanka and India would be the friendliest two nations.

People who live in Sri Lanka know the terrorism and how we lived. This young lady selling her country to make a career.

Correct me if I am wrong, isn’t the Sinhalese migrants from south India? Of course now they speak Sinhalese & they are Buddhist.

If not for discrimination, too.