“Hey shawty,” the recently-shaven, well-dressed, clearly-older-than-me man said as I crossed 34th street and made my way to Penn station. I was offended. “I’m 5’7,” I thought to myself, “and I am not short.”

Sensitive to height-based derogations, I turned around and leered at the man ready to defend my statistically backed, taller-than-average stature. He winked. “Oh,” I realized. “He’s catcalling me.” This man proceeded to walk behind me. “Is baby thirsty?” he asked. I first wondered if he meant for a refreshing drink on a hot summer day but gathered that his intentions were probably a little less PG and a little more XXX. I ducked into an alley and waited for him to leave.

Neither unique nor rare, my experience is one shared by females around the world. Street harassment, commonly perceived to be innocuous and often overlooked as a method of perpetuating pervasive sexism in everyday life, is considered to be any action or comment between strangers in public places that is disrespectful, unwelcome, threatening and/or harassing and is motivated by gender or sexual orientation. It can manifest itself as anything from whistles and honks to flashing and stalking or even, in more extreme cases, assault and murder. Twenty-five percent of women will experience street harassment by the age of 12 and 90 percent by the age of 19.

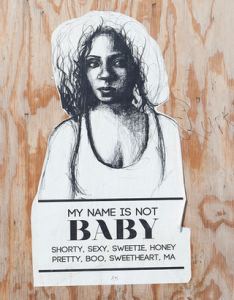

A few weeks ago, Brooklyn-based artist Tatyana Fazlalizadeh drew global attention during International Anti-Street Harassment Week when portraits from her series “Stop Telling Women to Smile” were plastered around the world. The series — comprised of solemn portraits of women and accompanied by phrases such as “My outfit is not an invitation” and “You are not entitled to my space” — is meant to address gender based street harassment and dissuade men from sexually harassing women on the street.

Fazlalizadeh began combating street harassment with street art in 2012 and gained widespread recognition for the project, which was named after a self-portrait of the artist with the message “Stop Telling Women to Smile” written underneath, in 2013. While traveling the country and speaking to women from a diverse set of geographic, economic and cultural backgrounds, she realized that the impact of street harassment remains constant even as the execution varies. If you are catcalled from a car amongst the sweet cherry blossoms of Washington D.C. or groped in a dark New York City subway car, you are still equally as likely to be left feeling “vulnerable and unsafe.”

Vulnerable. Unsafe. Violated. Threatened. Invaded. I find myself describing street harassment the same way I might describe rape. I, by no means, want to imply that the gravity of street harassment is equal to that of rape; however, the startling parallels are worth noting. A study in the Journal of Social Justice Research found links between street harassment and self-objectification in victims. Self-objectification occurs when we internalize the equating of our body’s worth with other people’s desires. Furthermore, numerous studies have found both correlations, which do imply causations, between self-objectification and increased rates of depression, anxiety and eating disorders — all of which are well-established side effects of rape.

I have mentioned a few American cities as popular locales for street harassment, but we mustn’t forget that this is just as much of an issue domestically as it is internationally.

Convinced by the sentiment that elevated rates of street harassment provide yet another example of women’s subpar human rights status, former president of Chile and executive director of United Nations Women, Michele Bachelet, reports, “[it] limits women’s freedom to get an education, to work, to participate in politics — or to simply enjoy their own neighbourhoods. Yet despite its prevalence, violence and harassment against women and girls in public spaces remains a largely neglected issue, with few laws or policies in place to address it.”

Barring support from women’s rights advocacy groups and various feminist organizations, Bachelet is absolutely right: There is a lack of seriousness in addressing street harassment. Victims are all too often told to take it as a joke or a compliment. Now I, depending on how aggressive I’m feeling, tend to respond to these incidents with cries of “fuck the patriarchy” and a foot chase of the perpetrator.

But the shawty situation was some years ago and I was not a well-equipped feminist at the time. So, flustered and afraid, I told my friends. They, in between laughs, said, “Someone thinks you’re hot. Be flattered.” A soft measure for a hard offense – no thank you.

Sometimes chalked up to cultural practice and other times blamed on our outfits, street harassment, in limiting the freedom and mobility of women, is, at the very least, an infringement on our safety.

In light of this realization, Stop Street Harassment surveyed 811 women in 2008 and found some alarming statistics.

Most commonly, women reported staying on guard as a protective measure. Eighty percent constantly assessed their surroundings while 69 percent avoided making eye contact and almost half wore certain clothes in hopes of attracting less attention in public. Next, women reported limiting their access to public spaces. Fifty percent admitted to taking an alternate route, 45 percent avoided being out after dark and 40 percent said they did not feel comfortable alone. Perhaps the most jarring of responses came from the 19 percent of women who reported moving neighborhoods and the 9 percent who stated that they changed jobs. All due to innocuous street harassment.

A severity in response indicates a severity in the nature of the original action. Suppose I were a black man. Suppose the original comment had been a certain racist, derogatory term instead of a sexist one. What would you think then? Passersby would likely have been outraged at the reference to racism, slavery, and hundreds of years of oppression, and rightfully so.

But “shawty,” an uncomfortable reminder of the objectification and subjugation of women, is considered acceptable nomenclature. Why? Racism, Stop Street Harassment argues, is simply more of an accepted wrong, so gender-based harassment does not elicit as strong of a response in comparison.

Fazlaizadeh took it upon herself to do something. She told CNN, “The main goal [of my art] is to make us rethink what’s considered normal and acceptable treatment of women.” In making this her goal, Tatyana’s eye-catching art provides a movement towards equality that is both nuanced in technique and momentous in impact.

So thank you, Tatyana. I’m tired of smiling too.

I disagree vehemently with your claim that racism is less tolerated in our society, and that people witnessing or hearing a racist exchange would have been “outraged” and intervened in a way that they would not if witnessing street harassment. People say racist things all the time and get away with it all the time (as the Brown University Micro/Aggressions Facebook page, as well as other campaigns like I, Too, Am Harvard clearly illustrate). That you imply that your life would somehow be easier, that you would be less harassed, as a black man is not only ludicrous, it’s highly offensive. I suggest you do some research on Stop & Frisk in NYC, but more broadly, incarceration rates of black men. I also encourage you to look into what scholars have called the White Girl Missing Syndrome and consider how the discrepancy in how, if at all, justice is enacted for violence against white women vs. black men.

I also suggest you read this: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/hollaback/replacing-sexism-with-rac_b_4896543.html