Gay marriage bans are falling like dominos, and not just in liberal states — first in Utah, then Oklahoma, Virginia and, most recently, Texas. These rulings, in addition to narrower rulings recognizing out-of-state same-sex marriages in Ohio and Kentucky, have elated gay marriage supporters across the country. But it’s important to note that the people didn’t make these decisions: federal judges did.

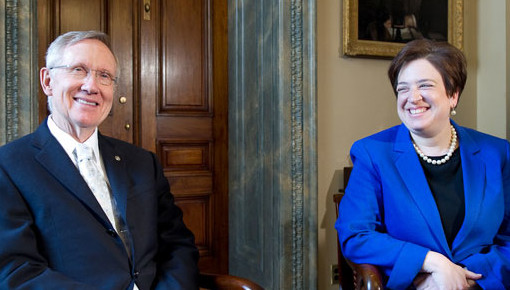

This distinction has important implications in a post-nuclear Senate. Months ago, Democrats invoked the “nuclear option,” ending filibusters on most executive office appointments and judicial nominees. Now, the majority party can vote on executive nominations, minus those to the Supreme Court, without achieving the 60-vote threshold needed in the past to overcome minority filibusters. The Democrats and Senator Majority Leader Harry Reid’s decision — the change to Senate rules in recent memory — caused reactionaries from both sides of the aisle to decry the “End of the Senate.” Some fear that filibusters on all sorts of legislation could be eliminated next, empowering the majority to avoid almost all minority opposition in the Senate. Whether a doomsday scenario like this will happen remains to be seen. But to find the rationale behind Reid and the Democrats’ decision, look no further than the recent federal court decisions on gay rights.

To be fair, the recent rulings are not a direct result of the nuclear option. None of the judges who made the rulings were confirmed after the Senate rules changed. Whether or not Reid had changed the structure of the Senate has had no direct influence on gay rights as of yet. However, these rulings do illustrate why political appointees are so important to a president’s long-term agenda. Unsurprisingly, all but one of the federal judges who struck down the gay marriage bans were appointed by either President Obama or Bill Clinton (the other was appointed by H.W. Bush). While the effects of political appointees are often unseen, the courts are one of the few venues in which presidents can continue to wield great influence after their terms are up. The rulings may seem to be a reflection of changing moods on gay marriage, and this is undoubtedly true to some degree. But it’s safe to say that the gay rights movement would be further back today without Democratic appointees sitting on federal benches.

With the filibuster in place, President Obama was unable to make his mark on the bench in a meaningful way. In fact, the tipping point for Reid seemed to come after Republicans moved to block Obama’s nominees to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. Though there were three vacancies on the court, Republicans refused to allow Obama to appoint new judges and restore the court to its normal size, arguing that judges already on the bench could manage the workload. What they failed to mention was that the court had a strong conservative majority that new, liberal judges would have overcome. Republicans didn’t take issue with the judges themselves, but rather used the filibuster to preserve the tilt of the D.C. Circuit Court.

In this way, the D.C. Circuit Court was a microcosm for federal courts in general. It’s common knowledge that there were almost as many filibusters under Obama as there were under all proceeding presidents combined. This meant that the administration consistently needed to either nominate judges with more centrist viewpoints or watch Senate confirmations slow to a creeping halt. And although the waiting period for a judicial nomination was about 70 days under President Reagan, that number has ballooned to about 7 months for Obama.

This posed a serious challenge for Obama’s executive agenda. During his time in office, Obama has made an effort to increase diversity in the judiciary. This initiative will have huge implications in the next decade, as federal courts will undoubtedly have to answer questions on affirmative action, gender equality in the workplace, mandatory minimums and other police enforcement mechanisms like Stop and Frisk. For Democrats, judicial appointments now are strikes for progress in the future.

Consider, then, the calculus that must have been going on in Reid’s head. Democrats faced a Republican party that had continued its knuckle-dragging on executive nominations. Obama’s domestic agenda had ground to almost a complete halt. The legislative and executive branches had been hampered by obstructionism for some time, but Republicans had now begun to seriously impact the shape of the judiciary. It wasn’t just Obama’s ability to execute his domestic agenda that Republicans were blocking; they were blocking his ability to leave a lasting impact through the courts.

Even though much has already been said about the dangers of Republican retribution and the threat to bipartisan cooperation in the face of this new dynamic in Congress, it’s understandable why Reid changed the rules. When weighed against the change in Senate decorum, the benefits to multiple aspects of the Obama agenda appeared more important.

Of course there’s a flipside to all of this. With a Republican president and majority in the Senate, they could erase any progress Obama has made on the bench. Just as Obama has appointed judges with more liberal positions, so the Republicans could appoint judges with hardline positions on abortion, gay rights and on issues of race and gender. Given their past history of ideological fervor on judicial nominations, Republicans could abuse the lower threshold more than the Democrats have so far.

Without filibusters, Democrats have been loath to rub salt in the wounds of Republicans by nominating extremely liberal judges. While the Republicans have retained some ability to stall judicial nominees in the post-nuclear Senate, Democrats have also angered their liberal bases by nominating judges that are considered too conservative. Since the “blue slip” custom on the Judiciary Committee allows Senators to veto judges representing their states, Obama has received flak for nominating judges who oppose abortion rights and support Voter ID laws to southern district courts.

In addition, conservative Democrats recently sided with Republicans to vote against one of Obama’s nominees who, 32 years ago, defended a Philadelphia man convicted of murdering a cop. He was the first nominee that Obama had failed to get confirmed since the rules change, and the administration is said to be furious. For contrast, look at the Republican Party’s history of nominating judges: Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas and, in particular, Robert Bork. All of these candidates were unflinchingly conservative and more contentious than their Democratic counterparts. More importantly, if the Republican party were to gain power, they would likely demonstrate more unanimity on supporting their president’s nominees. Harry Reid’s move, then, could backfire more than he expects or acknowledges.

If Harry Reid is right to believe that Republicans would have changed Senate rules anyway had they gained power faced obstruction from the Democrats, then these are moot points. But whether that would have been the case is an unanswerable question. It seems that the final verdict on the nuclear option will not be seen until the end of Obama’s term. Until then, Democrats will just have to sit back and pray for another win in 2016.