Increased citizen participation in government processes is a good thing – most of the time. Citizens interacting with the executive branch to initiate non-media highlighted issues is a good thing – most of the time. Improperly applied, though, these ideas can result in privilege-based discrimination and improper use of government resources. This is the case with the Obama administration’s website-based petition system.

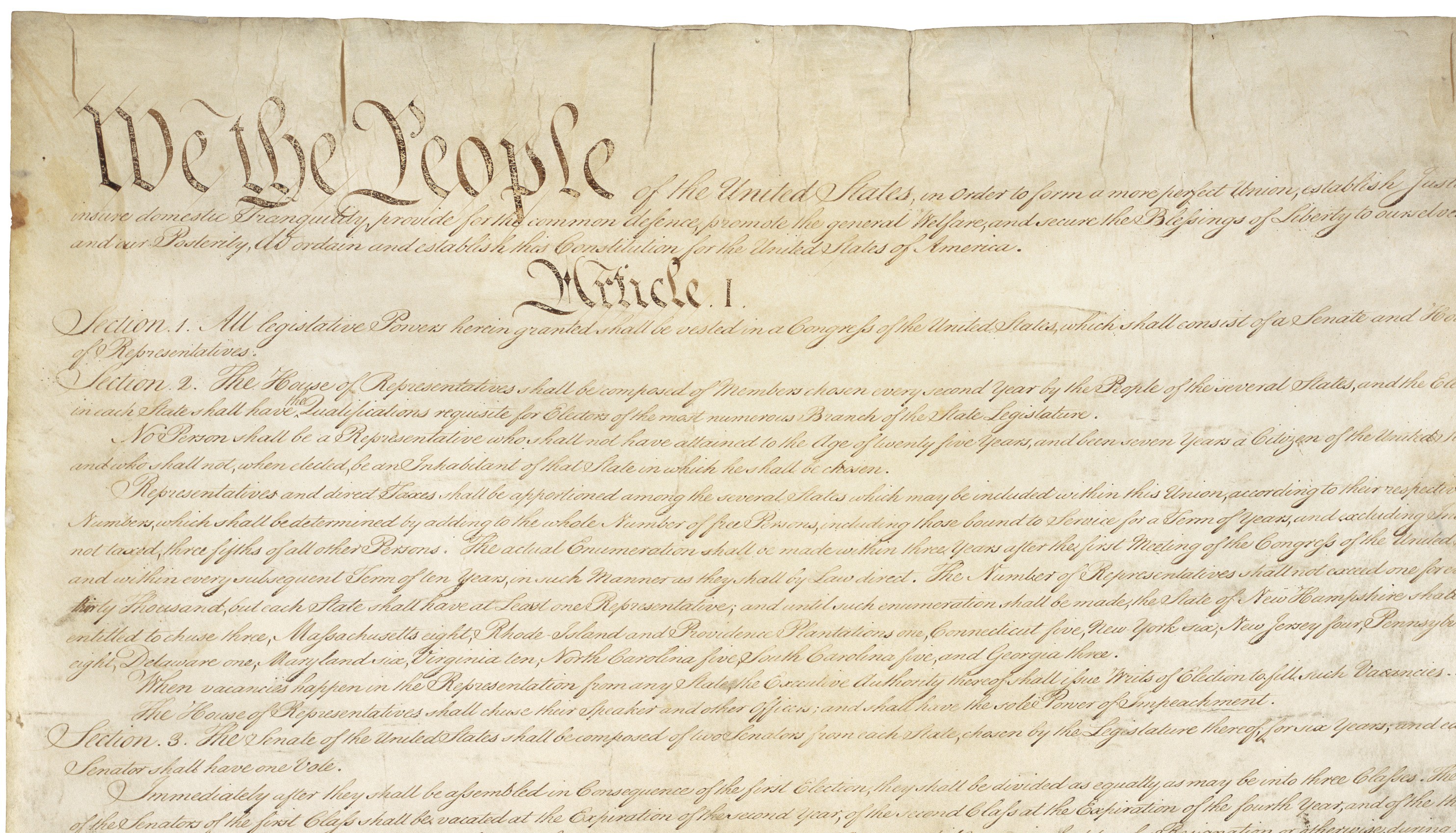

The United States Constitution establishes the right of citizens “to petition the Government for a redress of grievances,” a statement interpreted to mean that the executive branch must respond to citizen petitions. In the early years of the United States, several citizen-generated petitions led to important legislation, such as the 1789 Impost Act and the 1790 Patent Act. Both policies protected the economic rights of very specific citizen groups that would later grow into cornerstones of American legislation. More recently, though, petitions have reinforced already salient issues, such as Ukrainian violence, usually to little effect. The modern era has not made use of the right to petition the executive quite as effectively as the generation of our founding fathers did.

While a consistent governmental duty since the U.S. was founded, presidential responses to petitions were brought into the twenty-first century by the Obama administration in 2011. President Obama transitioned the petition and response process to the Internet with the website “We the People.” The website allows citizens to petition the government, “to address a problem, support or oppose a proposal, or otherwise change or continue federal government policy or actions.” The Obama administration uses the online service to expedite the signature process as well as the response process. A citizen can go on the website and search for petitions that align with his or her views. He has the option to either sign an existing petition or create a new petition representing his views. If any petition reaches 100,000 signatures in thirty days, a policy specialist from the Obama Administration will respond. The process is simple, with an easily navigated website and no-frills regulations.

As can be expected with the Internet, there have been several superficial requests, such as to “Declare the Monday after the super bowl ‘national hangover day’ and give Americans the day off work” or “Honor the great American horror movie star Vincent Price on a stamp.” Most recently, We the People has been the subject of media attention due to petitions to deport Justin Bieber. After the petition received over 260,000 signatures, the Obama Administration is obligated to respond to the requests. While this specific petition is ridiculous and inarguably a waste of limited government resources, it is also a prime example of the citizen-government communication that the site facilitates. White House responses are equally playful at times such as the publication of the White House Beer Recipe or declining to censor Jimmy Kimmel. Arguably, such efforts have more casually reinforced the ideal of public intervention in the way the government functions.

Regardless of the more infamous proposals, the majority of petition requests are issues important to American citizens that are not in the mass media or are not receiving sufficient attention at the federal level. Petitions for things such as changing the color of tow trucks’ headlights or making Election Day a national holiday draw presidential attention to small, specific interests. A recent trend in petitions is advocating for the condemnation of leaders of foreign countries for civil rights violations. For example, there are currently several petitions regarding the president of Uganda’s homophobic legislation.

The petition process is a valuable part of American democracy because it provides an avenue for the American people to directly address the executive branch, even though it has become less relevant in the modern age. The online procedure introduced by We The People creates race, age and income inequalities and therefore reduces and potentially eliminates the benefits of the petition process. Internet access is a prerequisite to creating a petition and therefore receiving a response. For Americans who do not have access to Internet or who do not have Internet in their homes, access to the government is automatically limited. Unfortunately, Internet access is highly stratified in the United States.

Concerning race, forty-two percent of Hispanics and forty-three percent of African Americans do not have Internet at home, compared to only twenty-eight percent of Whites and seventeen percent of Asians. As a result, Asian Americans are more than twice as likely to be represented in the petition-response process than Hispanic Americans and African Americans. Age wise, the older people are, the less likely they are to have the Internet in their home and even less likely they are to use the Internet at all. A whopping sixty-one percept of senior citizens do not have home broadband and forty-seven percent do not use the Internet at all. Nearly half of all American citizens over the age of sixty-five have no opportunity to use the petition-response process – a statistic especially worrisome when it comes to accepting only online petitions, considering that senior citizens are often the recipients of considerable government assistance. The most troubling data is that of income related discrepancies. For those with income less than $30,000, twenty-nine percent do not use the Internet at all while fifty-four percent don’t have home broadband. The higher a person’s income, the more likely he or she is to use and have regular access to the Internet. As an unintentional result, wealthier individuals’ values are given more weight in a democratic system that uses Internet based petitions. Nearly a third of citizens most likely to receive government assistance such as welfare, Medicaid, and unemployment insurance are unable to participate in a key government process.

We the People gives those most likely to already be represented well an even louder voice; it’s like cranking up the guitar amp from 4 to 11. Those less likely to be represented well cannot participate in the petition process, resulting not only in their exclusion from the political process but also their exclusion from potential policy. As they exist now, Internet-based political processes are inherently unequal because they represent the interests of the advantaged majority, while excluding citizens based on race, age and income. The Obama administration’s use of the We the People program has amplified Internet-based political inequalities and should be changed to include those currently excluded, either through an alternative program or through increased Internet access.

The current petition format amplifies the voices of the overrepresented. It also props up a system that has gone largely unused for the past century. Executive-citizen petitions have become fairly irrelevant, and President Obama’s efforts to make them salient once more have generated more inequality and misrepresentation. The effort to revamp the political process should be recognized as well intended, as We the People has definitely reinvigorated the petition process. However, the effort should also be recognized as more flawed than beneficial. We the People’s mixed reviews highlight an important evolutionary point of American politics – a political process created by the founding fathers at the birth of America is not sustainable in modern America. As America has grown and diversified, petitions are no longer a method of equality and representation. The Obama administration’s efforts were therefore a failed attempt to modernize an outdated political practice, making the resulting Internet inequalities misguided but hardly malicious.

Have our standards in education become so derelict and lax that even students from our Ivy League schools write so poorly? Not only was the argument on the subject matter questionable, but the syntax, diction, and grammar made it painful to read! This is the first time I’ve read an article from the Brown Political review. I am the daughter of a Brown graduate and quite frankly, I’m leaving this site disappointed… I suppose I just had lofty expectations for anything published under the Brown name. Perhaps I may have just been convinced that I should eschew reading future published articles.