Born in 1930, John Jay Hooker (D) is a successful businessman, a frequent litigant and one-time political candidate. In the late 1990s and again this year, Hooker has filed a case with the Tennessee Supreme Court contending that the current process of appointing judges to Tennessee state courts is unconstitutional. Under this system, which applies to vacancies in the Tennessee Supreme Court, the State Court of Appeals, and the State Court of Criminal Appeals, the Governor makes judicial appointments based on a list of nominees chosen and vetted by the state’s Judicial Nominating Commission. Those appointments are then offered to the public for retention or rejection at the following general election. Tennessee’s constitution provides that judicial candidates be elected to office by the public, but under the current system, justices appointed to the courts may begin serving their terms well before the public has the opportunity to vote on their candidacy. The argument can be made that the process helps to make state judgeships independent of the financial and political pressures that characterize other major elected offices. Given that many judicial appointments must be made between general elections, some have also implied that the system is not only constitutional but practical. However, Hooker and his supporters argue that the process denies the public its right to elect its judges. As he states in an interview (only five minutes long and worth seeing) conducted by TN Report in August, “The people are the monarch, the people are the boss – not some politician who appoints judges.”

Born in 1930, John Jay Hooker (D) is a successful businessman, a frequent litigant and one-time political candidate. In the late 1990s and again this year, Hooker has filed a case with the Tennessee Supreme Court contending that the current process of appointing judges to Tennessee state courts is unconstitutional. Under this system, which applies to vacancies in the Tennessee Supreme Court, the State Court of Appeals, and the State Court of Criminal Appeals, the Governor makes judicial appointments based on a list of nominees chosen and vetted by the state’s Judicial Nominating Commission. Those appointments are then offered to the public for retention or rejection at the following general election. Tennessee’s constitution provides that judicial candidates be elected to office by the public, but under the current system, justices appointed to the courts may begin serving their terms well before the public has the opportunity to vote on their candidacy. The argument can be made that the process helps to make state judgeships independent of the financial and political pressures that characterize other major elected offices. Given that many judicial appointments must be made between general elections, some have also implied that the system is not only constitutional but practical. However, Hooker and his supporters argue that the process denies the public its right to elect its judges. As he states in an interview (only five minutes long and worth seeing) conducted by TN Report in August, “The people are the monarch, the people are the boss – not some politician who appoints judges.”

But here is the fun part. Although the colorful nature of the primary litigant has ensured some level of attention for the issue in Tennessee, what has really grabbed headlines in the state and the region is the Governor’s challenge in finding judges who can and will hear the case. Not only has the entire Tennessee Supreme Court recused itself from Hooker v. Haslam (Bill Haslam being the current Tennessee Governor), but three of the five members of the Special Supreme Court appointed by the Governor to replace them have now withdrawn from the case.

Tennessee is not the only state to grapple (sometimes with absurd results) with the policies and processes surrounding judicial elections and appointments. On a federal level, the failure of the U.S. Senate to fill judiciary vacancies in Rhode Island made it necessary in 2011 to outsource more than twenty Rhode Island civil cases to Massachusetts and New Hampshire. And while the non-profit watchdog organization State Integrity gave Tennessee a B for Judicial Accountability, Rhode Island earned a solid D-. This assessment follows the 1994 overhaul of Rhode Island’s system for judiciary appointments, in which a “merit selection system” was instituted to replace the existing appointment process, which was perceived as corrupt and vulnerable to abuse. The new system requires that the Governor select judicial appointees from among a list vetted and provided by an independent Judicial Nominating Commission before being confirmed by the General Assembly. However, it is important to note that the new system did (and does) not apply to the process for selecting Magistrates, who serve in 10-year terms, renewed contingent on the decision of the appointing authority.

Rhode Island’s judicial selection system was further modified in 2007, when Governor Carcieri signed legislation allowing the Governor to select justices from among not only the 3-5 nominees presented by the independent commission for a specific vacancy but from among any of those nominated by the JNC within the last five years. Common Cause, a non-profit judicial reform organization, notes that this change has weakened the authority of the JNC, but the modification, which was initially scheduled to sunset in 2008, has nevertheless been renewed by the General Assembly each year for the last five years.

During the 2010 Rhode Island gubernatorial race, then-Senator Lincoln Chafee expressed concern over the way that this system was being implemented. At the time, Carcieri had exceeded 21-day deadlines for addressing multiple vacancies on the Rhode Island District, Superior and Family Courts, and Chafee was quoted as criticizing “the judicial selection process that has allowed Governor Carcieri to leave appointments open until the final days of his administration.” Chafee specifically endorsed a review of the judicial nomination and appointment process in Rhode Island, stating that, “Deferring appointments for so long has created the suspicion that cronyism and political favors will drive the Governor’s decision making.” He argued that then-Governor Carcieri should not make additional judicial appointments before the end of his term in office because, “Such appointments would further shake the confidence of Rhode Islanders in the integrity of their government, as well as represent a significant, permanent increase in judicial expenditures for salary, fringe benefits, and support services.” Not surprisingly, Carcieri did not hesitate to proceed with the judicial appointment process for several candidates.

However, a year after Chafee’s inauguration as Rhode Island’s new governor, he was receiving criticism for his own failure to fill long-standing vacancies on the state’s courts. WPRI reported that Chafee “didn’t put a single jurist on the bench during his first year in office,” even as the vacancy count continued to rise. A spokesperson for Common Cause, a non-profit judicial reform organization, was quoted in the same article stating, “It has been asserted that judicial vacancies are being used as bargaining chips with the legislature, and that undermines the whole purpose of having a merit selection system.” Meanwhile, Rhode Island NPR quoted Chafee as saying, “I’m aware that there’s a lot of back and forth with the General Assembly on these coveted judgeships…My goal is to get the best people on the bench, and that’s good for Rhode Island’s reputation.”

In June of this year, the Rhode Island Senate Judiciary Committee approved three new judicial appointments by Governor Chafee, among the first since he entered office in 2010. I haven’t seen any criticisms of these particular appointments. But as of August, there were again four new vacancies on the state courts, each to be filled by appointment of the Governor.

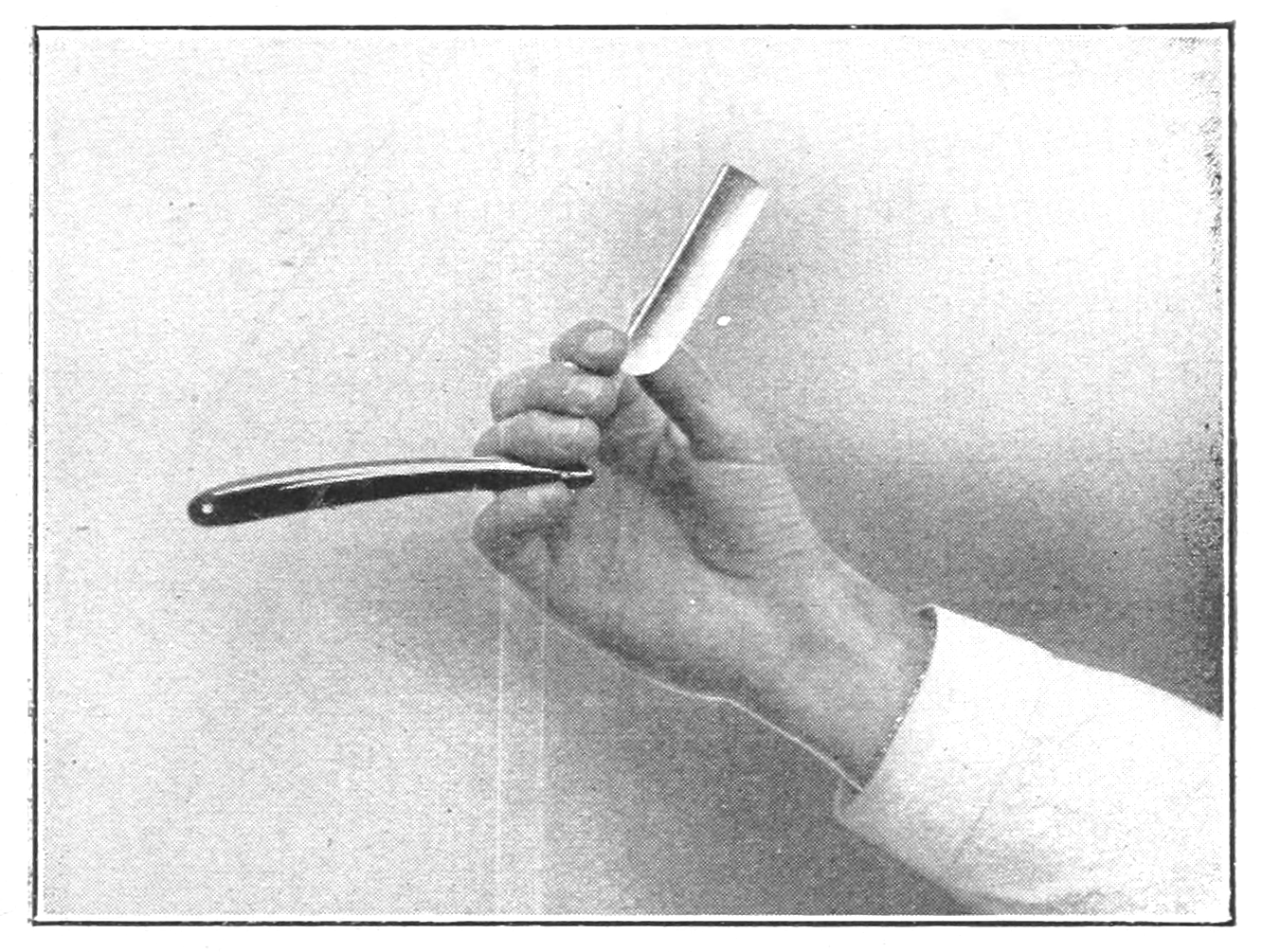

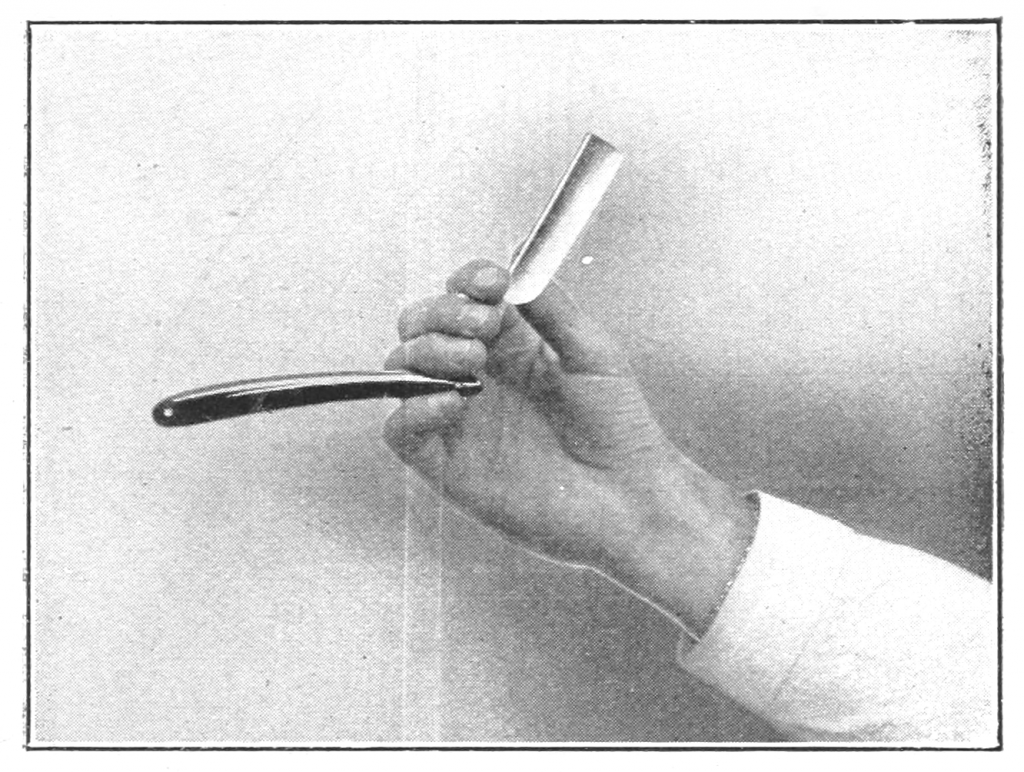

Our judicial system might be over 200 years old, but clearly we’ve yet to work out all of the kinks. And who is the right person to fix it? The governor who appoints our judges? The citizen who elects her? The congressional body that appoints members of the nominating boards and confirms the governor’s appointments? The judge who serves as Senator before receiving his life-long appointment to the court? In fifth grade, the concept of checks and balances among the three branches of government seemed so intuitive and so simple. But when the governor is appointing judges to replace the judges who replaced the judges who recused themselves from the case addressing the legality of the laws created by the General Assembly to govern the governor’s appointment of the judges, who is left to shave the barber?