President Donald Trump’s use of Twitter is generally portrayed in the media as a paradigmatic shift in presidential communication — so unprecedented that it has forced us to make fundamental, consequential decisions on the role of social networks in modern politics. Later this year, a New York District Court will hand down one such decision: Does the President blocking people on Twitter raise a legitimate First Amendment issue?

On June 6, The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University sent a letter to the White House on behalf of seven Twitter users who, the Institute claimed, had been blocked by the President for criticizing him and his actions. The authors of the letter spelled out their argument clearly: “Blocking users from your account violates the First Amendment. When the government makes a space available to the public at large for the purpose of expressive activity, it creates a public forum from which it may not constitutionally exclude individuals on the basis of viewpoint.”

The letter did not explicitly threaten legal action, but only asked that the users be un-blocked. However, when their request went unanswered by the White House, the Knight Instituted decided to file a lawsuit on First Amendment grounds on behalf of the users. A decision in the case could come as soon as October, although it certainly seems possible that a ruling either way might be appealed up to higher courts.

The Knight Institute makes a compelling argument, one that raises important questions about the role of social media in politics and American society going forward. However, the claim seems to fall short on three fundamental points — that being blocked on Twitter curtails freedom of speech, that Trump’s Twitter is clearly a public forum and that he isn’t free to use a private social media platform as he pleases. A decision in the Knight Institute’s favor, in spite of its weak argument, would be a drastic overreach that could open the floodgates to further entanglement of government in social media networks, fundamentally changing the way users enjoy these platforms forever.

Blocking a user on Twitter is hardly the drastic limitation on speech that Knight argues it to be. In the words of the company itself, the blocking feature “helps users in restricting specific accounts from contacting them, seeing their Tweets, and following them.” This means that the users blocked by Trump are unable to follow him, see his Tweets through searching or on his feed, view his profile and participate in the comments section of his posts. Many of these blocked users were consistently active in the replies section of Trump tweets, collecting retweets and favorites for their criticisms of the President; That is, until the seven users found themselves blocked.

The White House chose not to contest the point that Trump blocked the users because of their political viewpoints. This concession was touted as a win for Knight’s cause, and it certainly doesn’t hurt it. The Justice Department was quick — and correct — to point out, though, that the users could still view all of Trump’s tweets while logged out and express their opinions on their account or through several other outlets. That isn’t to mention that sites like http://www.trumptwitterarchive.com/ give real-time updates of the President’s feed for anyone with or without an account to see and even allows for easier searching among past tweets than than Twitter.com or the mobile app itself. Furthermore, the mainstream media, which has, over the course of Trump’s candidacy and his first term as president, systematically lowered the bar for what is to be considered “breaking news”, reports just about all of Trump’s tweets, no matter the subject.

It is estimated now that there are 68 million Twitter users in the United States, all of which have different interests and come to the site for a range of different reasons, whether it be sports, politics, music or business. The fact that over 1/5th of the US population uses Twitter is remarkable for the company itself, but the existence of a variety of other ways to both express and consume political speech give little merit to the argument that being blocked is a First Amendment slight. The remaining 80 percent not on Twitter find another way to consume and discuss political happenings, and those who find themselves blocked now must do the same. Following Knight’s logic, should every politician using social media be made responsible for ensuring that all of their constituents see every Tweet they send out, even if those constituents already consume political news elsewhere?

A second essential claim Knight attempts to make in support of their argument is that Trump’s account constitutes a public forum. The “town hall meeting” is the go-to analogy in many free speech debates, but whether Twitter fits as a direct comparison is questionable. Knight’s original letter gives a loose definition of a public forum: “When the government makes a space available to the public at large for the purpose of expressive activity.” A town hall meeting undoubtedly fits this definition, but Twitter, a social media network produced by a private company, does not.

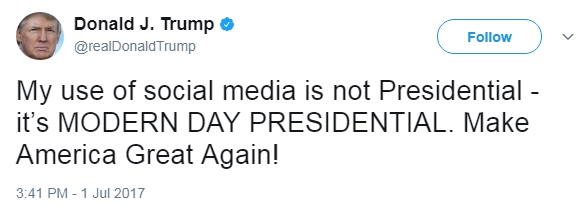

The claim might be argued for on the grounds that Trump’s particular style on Twitter is blurring the lines between the network as a private company and public platform. Every Congressman and nearly every governor is now on Twitter, but they don’t use it as forcefully as Trump and therefore don’t require judicial strong-arming, the argument goes. Trump himself vaguely claimed that his use of Twitter is “Modern Day Presidential.” He also previously defended his Twitter use by claiming that it allows him communicate directly with the people and circumvent “fake news” outlets.

Ultimately, it’s important not to disconnect Trump’s actions on Twitter from his personality in general. His vulgarity, impulsivity and the way in which these are perfectly amplified in 140-character bursts pre-date his political career by several years. The reason Trump’s Twitter use is unprecedented is because Trump himself is unprecedented. Rather than tying Twitter up in judicial regulation, concern ought to direct toward constitutionally questionable policies like Trump’s immigration ban or his recent threat to revoke licenses from news networks.

One does not need to agree with Trump’s use of Twitter, or the things he says on it, to believe that he has the right to use it how he wishes and that enforcement to the contrary could have disastrous consequences. Former Trump advisor Steve Bannon, a prominent Alt-Right figure, previously advocated that companies like Facebook and Google ought to be regulated like public utilities. A decision in favor of the Knight Institute in this case would be the along the same vein, welcoming unnecessary governmental regulation of social media and tech companies. Being unable to send snarky replies or innocent gifs to the President pales in comparison to the free speech and illegal surveillance concerns that would arise with greater government control of outlets like Facebook or Twitter. A judicial victory for Knight would send us down this road, which is why the plaintiffs’ shaky case should be brought down in court. Trump is stooping to unsurprising levels of pettiness in blocking critical opponents on Twitter — but it would be a grave mistake to strip him of the right to do so.