Over the past few years, the European Union has become increasingly vocal in its criticism of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, particularly as it relates to settlement policy in the West Bank. While this shift in European-Israeli relations has resulted only in exchanges of veiled threats, Israel has responded with alarm and frustration. The European community, on the other hand, considers this change of posture little more than an overdue moral recentering. Perhaps that’s all it is, but this development has already produced a slew of ancillary consequences for European security and global stability that policymakers should find troubling.

Every few months, the EU gives Israel a little political prodding as a reminder that it hasn’t forgotten about the Palestinians’ horrific living conditions and the Israeli policies that perpetuate them. And each time the Israeli government sees the EU discussing proposals requiring the labeling of goods produced in the West Bank or circulating diplomatic memos suggesting restrictions on trade, it gets understandably unnerved. The EU is Israel’s largest regional trading partner, and new data on the impact of ongoing European boycott and divestment activism demonstrate the magnitude of the economic pressure Israel already faces from a frustrated Europe. Last year, for example, Jordan Valley farmers saw a 14 percent drop in revenue, largely as a result of European boycotts. In light of these circumstances, it’s easy to understand the Israeli leadership’s concern about how European policies might impact Israel’s economy. Consequently, Israel has begun to establish new economic partnerships outside of Europe that could prove geopolitically disadvantageous to the West.

In the aftermath of the 2010 discovery of the Leviathan natural gas deposits off of Israel’s Mediterranean coast, for instance, Russia pushed the Israeli government for an energy partnership. The terms of the subsequent negotiations between Russia’s state oil and gas company, Gazprom, and the Israeli government have long been the subject of rumors, among them the accusation by members of the Israeli Knesset that Russia offered to stop exporting advanced weapons to the Assad regime in Syria in exchange for an Israeli commitment not to export gas to Europe. Moreover, Israeli officials have confirmed that Gazprom pursued several positions on the Leviathan license and submitted a high bid for a 30 percent stake in the field’s ownership. Throughout the negotiations, Gazprom’s expressed intention was to export Leviathan’s gas throughout the Middle East and East Asia. The company has further moved to set up a subsidiary in Israel, and in 2013, Gazprom signed a letter of intent to help finance an offshore liquefied natural gas facility drawing from the Tamar gas field, also in the Mediterranean, to which it now has exclusive export rights.

Europe shouldn’t take this lightly. For years, Europe was Gazprom’s biggest export market, accounting for 40 percent of the company’s revenue in 2013. This interdependency has since turned problematic for both Europe and Gazprom. On Gazprom’s end, there are concerns that Israel’s entry into European gas markets would severely undermine the company’s market power. For its part, Europe has been troubled by its dependence on Russian energy for over a decade, and those worries have only been exacerbated by the recent tension in Euro-Russian relations. While access to Israeli gas deposits would go a long way toward helping insulate Europe from Russian influence, it’s hard to ask Israel to resist Russian solicitations when European language threatens trade restrictions.

More recently, Russian-Israeli cooperation has stalled, though Russian gas company SoyuzNefteGaz has entered into an agreement with Syria to support the development of its offshore deposits. Furthermore, Israeli gas development generally has stagnated due to a maritime border dispute with Lebanon and an antitrust controversy that divided Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s government. In spite of this, there is momentum in Israel to accelerate gas production sooner rather than later because of predictions that the lifting of sanctions on Iran will cause global energy prices to plummet. Europe would do well to keep Israel’s energy ambitions on its radar, for Russia remains eager to buy control of the enterprise.

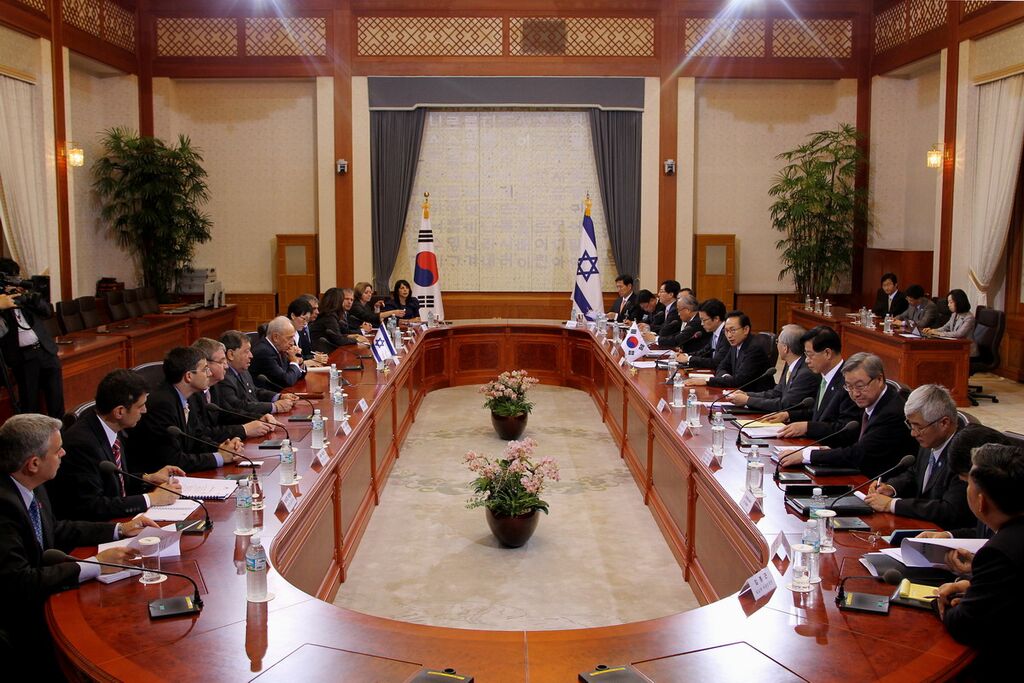

Israel has been seeking new economic partners in sectors unrelated to energy as well. Countries across South and East Asia — including China, India, South Korea and Japan — have been flooding Israel’s economy with new investment and expanding the scale of their trade with the country. This money has flowed into a wide variety of industries, ranging from food production and pharmaceuticals to weapons and technology. Just last year, Israel welcomed nearly $4 billion of Chinese investment, and between 2009 and 2014, Israeli technology exports to China increased by 170 percent. Japan has entered the race, too, with a 500 percent increase in investment in Israel between 2012 and 2014. Japan’s annual totals, however, have yet to exceed $10 million of direct investment. Accordingly, today, China is poised to overtake the United States as the largest foreign investor in the Israeli technology industry. Moreover, though a quarter of Israel’s exports go to Asia at present, projections indicate that trade with the region will soon outpace trade with Europe and the United States. And with steps in place to normalize trade relations with major economies across Asia, trade volume is expected to increase dramatically in the near future. Indeed, there is talk in the Israeli government of expanding trade with Asia — already around $20 billion annually — to up to ten times its current volume within the next several years.

This shift may prove troublesome for Europe for a few reasons. First, while some of the technologies Israel has started selling to these Asian economies are used to accelerate desalination or to enhance cybersecurity, many of them are used to kill people. Asia is Israel’s largest export market for military technology, with annual purchases of around $4 billion for several years running. Israel is India’s second largest source of arms; weapons deals between the two nations are responsible for upwards of $1 billion of Israeli exports each year, making India the world’s top purchaser of Israeli arms by a fair margin. This exchange of advanced military technology should concern Western states hoping to check the potential escalation of India’s longstanding conflict with Pakistan. Additionally, India’s purchases from Israel may prompt Pakistan to further pursue its own arms buildup, which, given regional instability and pressing economic development needs, would be unfortunate. Furthermore, if the West hopes to stem burgeoning Japanese remilitarization or prevent China from gaining access to cutting edge military technologies (both of which would help avoid war over the South and East China Seas), it has good reason to be concerned about Israel’s weapons dealings expanding to those two countries.

These arms agreements play into a broader pattern of the West losing diplomatic control over both Israel and its Asian partners as they grow closer. Little captures this dynamic better than Israel’s eagerness to join China’s newly established Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Conceived in response to Chinese frustrations with American rulemaking at the World Bank and Japanese rulemaking at the Asian Development Bank, the AIIB is a Chinese effort to sponsor global development according to its own agenda, through an institution at which it has the plurality of votes and the ability to make its own rules. The fact that Israel joined the AIIB in spite of American opposition exemplifies the West’s recent loss of influence over Israel.

The political implications of this can also be seen at the UN. India, for instance, shocked many in early July by breaking its historically pro-Arab voting streak to abstain (along with just four other countries) from a vote of the UN Human Rights Council condemning Israel for its handling of last summer’s conflict in Gaza. The United States was the only country to vote against the condemnation. While this is a new step for India, Japan and South Korea have a history of abstaining from UN votes critical of Israel. The impetus for this silence is clear. In India’s case, it was almost certainly moved by its substantial defense partnership with Israel. India’s changing ties were also apparent last March, when Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was nearly alone among world leaders in expressing public pleasure at Netanyahu’s recent reelection.

To those who view the economic isolation of Israel by the West as a moral imperative, these ancillary harms are unlikely to be meaningful. And perhaps Israel will recognize that European governments aren’t ready to move their responses to the Palestinian crisis beyond token gestures acknowledging negative public sentiment on the ground. That said, the current lay of the land shows an ever-cautious Israel preparing for the possibility of an end to full-fledged Western support with understandably little regard for the geopolitical impacts this preparation will have on the interests of its Western partners. So while the measure of these consequences might be irrelevant to the moral weight of the humanitarian crisis in Palestine, the EU should understand that it may wake up in 2020 to find that the Israeli government doesn’t particularly care where Europe directs its business. It should understand that Russian and Chinese leverage will only increase with time. And it should consider whether the strategic realities of the present permit such a rigorous moral stance. Perhaps they do, but the risks are substantial.