In releasing his new album “To Pimp a Butterfly,” Kendrick Lamar topped off a year of political and racial turmoil with an appropriately radical, incisive work of art. The album weaves together personal narratives with political thought on issues from colorism to the commodification of musicians. With biting lines like, “They tell me it’s a new gang in town/From Compton to Congress…ain’t nothing but a flu of new DemoCrips and ReBloodlicans/ Red state versus a blue state, which one you fightin’ for?” the album solidifies Lamar’s position as one of the leading voices in a new generation of rappers, one that is speaking out to millennials about injustice in the United States. His album’s debut at #1 on the Billboard 200 chart confirmed a sweeping change in the hip-hop industry. The genre is once again brazenly political.

In the past six months, rappers have released a plethora of songs advocating political change. In “The Blacker the Berry,” for example, Lamar confronts black self-hatred and institutional racism with lines like, “I mean it’s evident that I’m irrelevant to society/That’s what you’re telling me, a penitentiary would only hire me.” Since Michael Brown was killed by police officer Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri, many rappers have taken up similar themes. J. Cole, another one of hip-hop’s leading voices, traveled to Ferguson one week after Brown’s death and marched in local protests. Afterwards, he released a song dedicated to Brown titled “Be Free.” The song is a heart-wrenching plea for peace, with Cole singing, “Can you tell me why/Every time I step outside I see my niggas die?/I’m letting you know/That there ain’t no gun they can make that can kill my soul.”

Significantly, Cole and Lamar are two of the most commercially successful rappers in the industry, unlike some other more overtly political artists. Cole’s three most recent albums were all certified gold by the RIAA. Lamar’s first album, “Good Kid M.A.A.D City,” sold over one million copies. Rather than becoming mired in the tropes of violence, drugs and misogyny for which commercialized hip-hop is often criticized, the two artists rail against them. Lamar has drawn many comparisons to the late Tupac Shakur, who dominated hip-hop in the 1990s with his socially-conscious rap, as his generation’s West Coast prophet.

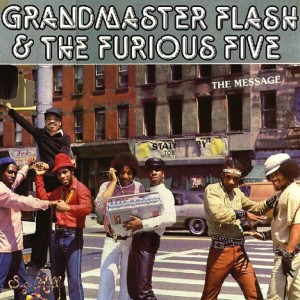

Hip-hop artists’ recent political focus is nothing new. Indeed, the role of rapper as social critic goes back decades, to the very foundation of hip-hop. Some people trace its roots to the rhyming games that earlier African-Americans used to resist slavery and other systems of oppression. This form of creative resistance itself originated in the oral tradition of West Africa, where storytellers called griots were responsible for entertaining and for maintaining tribal and family histories. Whether or not it was a direct descendant of these traditions, rap rose to prominence in the South Bronx during the 1970s in an environment of social and political oppression. This was the era of Reaganomics, of deindustrialization, and of the racialized urban ghetto. The predominantly African-American South Bronx, like many other urban neighborhoods across the country, was ravaged by crime and unemployment, along with many other forms of deprivation. Many early rap songs coming out of the South Bronx addressed this desperation, and hip-hop culture quickly spread to other urban communities under similar conditions. For example, the 1982 song “The Message” by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five decries the poor education, drug addiction, and physical disrepair that plagued the South Bronx: “I got a bum education, double-digit inflation…I can’t walk through the park ‘cause it’s crazy after dark.”

It wasn’t long before hip-hop artists became popular in mainstream America, and their roles as political leaders diminished. Cultural critics claim that white record label executives, as they signed hip-hop artists, altered their product to appeal to a wider market, and in doing so stripped hip-hop of its political power. Derek Ide, the Social Movement Studies Department Chair at the Hampton Institute, writes that because political dissidence was not attractive to the majority of American consumers, hip-hop became separated into “two worlds:” one of commodified mainstream rap, and one of political, socially-conscious rap that is not as commercially viable. While “underground” hip-hop continues to be politically charged, mainstream hip-hop is often directed at parties, centering itself on themes of materialism. A quick glance at the lyrics of songs on Billboard’s Top Rap Songs list makes this clear: the number one song, “Trap Queen,” is about rapper Fetty Wap’s conflicts with a gold-digging girlfriend. “Time of Our Lives” and “G.D.F.R,” the second and third ranked songs, are both party-anthems.

Rap stalwarts J. Cole and Kendrick Lamar have managed to bridge these two separate worlds, much like other exceptional rappers in the past. Tupac is exalted as a model of the politically-conscious, commercially successful rapper. In recent years, artists like Kanye West, Lauryn Hill, and Talib Kweli have all enjoyed financial success while speaking out against social and political issues afflicting African-Americans. In a recent New York Times editorial, writer Jay Caspian Kang hailed Kendrick Lamar as the new “Hip-Hop Messiah,” a spiritual leader of hip-hop that only comes around every few years. Of this imaginary role, he writes, “His work must feel political, but not overtly political. He should be an example and a savior to the young black people who listen to his music.”

Lamar, straddling the commercial and the political, occupies a precarious position. Although vastly popular activist rappers like Lamar are rare, they have historically risen to the occasion during moments of desperation for communities of color. In the 1980s, as a crack epidemic afflicted poor African-American communities in New York, rap group Public Enemy created a career with political music, including songs like “Night of the Living Baseheads,” which portrays the deleterious effects of crack on users in African-American communities.

The recent focus on racial divisions in light of Ferguson is a logical continuation of this tradition. In fact, it is not particularly novel; hip-hop has a long history of voicing anger against police racism, and today’s political climate is no different. The phrase “Fuck the Police,” now ubiquitous in anti-police brutality protests, has its origins in N.W.A.’s 1988 eponymous breakthrough song. During the 1990s, after Rodney King was beaten by police in Los Angeles, Ice-T released a controversial song “Cop Killer” that addressed police racism in the United States. Fear of the songs’ consequences among politicians and law enforcement officials was so great that they lead protests calling for a ban of Ice-T’s songs.

Since the death of Michael Brown last August and the subsequent protests of his death, the United States has been forced to examine the human rights crisis of police brutality. It is no surprise that rappers, figures with a history of political activism, are responding to this moment of necessity with political music. This alone does not make them into “hip-hop messiahs.” The J.Coles and Kendrick Lamars of the world are unique because they possess not only the awareness of political scientists, but also the widespread appeal of pop stars. In using their popularity to decry racist policing, they prompt millions of listeners to examine political issues. They take ideas often confined to underground circles and present them to a huge body of listeners hungry for change.

As they have so many times before, rappers are emerging as the voices of a disenfranchised population. Some, like rapper Questlove, say that hip-hop artists are not doing as much as they should. In an Instagram post four months ago, he wrote, “I urge and challenge musicians and artists alike to push themselves to be a voice of the times that we live in.” Whether or not rappers’ efforts are adequate, Questlove’s post makes one thing clear: they are once again heralded as leaders in a moment of great suffering. In The Blacker the Berry, Lamar says, “This plot is bigger than me, it’s generational hatred.” If Americans feel powerless in the face of political oppression, these rappers’ star power employed in the name of social justice may be exactly what they need.