If a win-win situation ever existed in politics, the Rhode Island governor’s race might be it. Both candidates — Republican Allan Fung, mayor of Cranston, and Democrat Gina Raimondo, Rhode Island’s General Treasurer — are members of politically underrepresented groups as well as native Rhode Islanders. Regardless of who wins this year’s gubernatorial race, Rhode Island’s government will uncontestably be moving forwards in terms of diversity: Fung would be the state’s first Asian-American governor and Raimondo its first female one. However, these two distinctly 21st-century politicians are facing age-old questions: Who has the more coherent vision for the state? Which candidate is better suited to handle education policy and fight poverty? And who can better propel Rhode Island into a position of economic progress and growth after years of post-recession stagnation?

The Contenders:

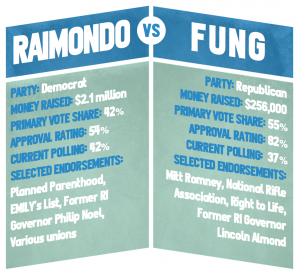

In one corner stands Raimondo, the favorite, with a bachelor’s degree in economics from Harvard and a law degree from Yale. In the other, Fung — the loyal son — who remained in the state to study political science at Rhode Island College before earning a law degree from Suffolk University. Raimondo is known for her strong uppercut: legal experience in the district courts and a corporate background. She is backed by the solid credential of founding Rhode Island’s first venture capitalist firm. Fung, however, is an experienced fighter who can parry blows on the legal front — his stint as a special assistant attorney general preceded his tenure as lobbyist for the Government Relations Counsel at MetLife. Fung comes into the race carrying belts from smaller prizefights, having served as one of Cranston’s three city-wide councilmen for four years before becoming mayor of Cranston.

In this fight, the partisan tropes are flipped: The venture capitalist candidate is the Democrat, while the Republican candidate has spent his life in the public sector. In either case, their experience leaves both Raimondo and Fung eminently qualified to serve as governor of Rhode Island — at least on paper. They have distinguished public service backgrounds and records to draw upon. The true concern revolves around who possesses the vision and political gravitas to make waves in the Ocean State.

The Economic State of the State:

Rhode Island never really recovered from the 2008 financial crisis. Whether you’re traversing the cracked streets of Olneyville or passing one of the foreclosed houses that litter the state, it’s clear that the recession’s lingering stagnation still claims a tight grip on the state. Until August 2014, Rhode Island had an 8 percent unemployment rate — the highest in the country. While the rate has since declined to 7.7 percent, that only brings the state down to the third-highest spot nationally, just outpacing Georgia and Mississippi. One in five children in Rhode Island lives in poverty. Moreover, the 2014 ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index ranked Rhode Island 41st in the nation in terms of positive economic outlook.

Residents are understandably frustrated with the current state of affairs, but it seems that negativity has taken on a special character in Rhode Island. A recent Gallup poll showed that Rhode Island residents are the least enthusiastic Americans when it comes to their home state: Almost one in five Rhode Islanders says that their state is the worst place to live. The future governor is, then, tasked with not only revving up economic activity, but also rekindling state pride.

At the core of this malaise are the poor economic prospects for Rhode Islanders today and the state government’s inability to initiate effective reform. Unsurprisingly, Fung and Raimondo have made economic policy the central issue of their campaigns. Both candidates have first-hand experience attempting to stimulate Rhode Island’s economy. While Raimondo’s role as general treasurer might constitute more obvious experience — she spearheaded key reform agreements regarding pensions in 2011 and unions in 2013 — Fung is not lacking in experience either. Like the rest of Rhode Island, Cranston was hit hard by the recession. But Fung points out that his city’s employment rate is slightly higher than that of the state as a whole, and he attributes these results to his pro-growth policies. It is left to be seen whether Raimondo and Fung can recreate these successes under their belts while sitting in the governor’s mansion.

Fung offers a diverse selection of economic solutions to Rhode Island’s struggle. Across the board, he has consistently emphasized his role in downsizing Cranston’s government and implementing cost-cutting reforms that, he claims, stimulated small businesses and created 1,000 new jobs. In an April 2014 letter published by the Providence Journal, Fung says that Cranston’s “remarkable turnaround” can be directly linked to the budget proposal he crafted, which “meets day-to-day expenses, invests in education and long-term fiscal stability, and maintains a healthy rainy day fund.” When Fung took office as mayor of Cranston in 2009 at the height of the recession, he inherited a 10.5 percent unemployment rate (Rhode Island’s unemployment rate at the time was 9.7 percent). That rate may seem high, but other cities fared even worse: Providence’s unemployment rate hit an all-time high of 15 percent in July 2011. Ultimately, Fung’s administration has seen Cranston’s unemployment rate plummet to 7.1 percent.

As governor, Fung promises stimulatory tax relief in the form of a $200 million tax reduction package to help boost job growth and small business prospects. The package centers around corporate taxes in the hopes of making Rhode Island “one of the most competitive states for business taxes and business friendliness” in the region. Currently the state’s corporate tax is 9 percent; Fung’s proposal aims to lower it to just 6.5 percent within his first year, which would make it the lowest rate in the Northeast.

For many, Fung’s plan ignores the benefits that more robust government action can bring to an economy, something Raimondo’s plan embraces. Her platform combines some of Fung’s private-sector flair with serious government initiatives, including numerous job-creation policy proposals. Raimondo’s central economic policies propose establishing support networks and programs for Rhode Island businesses and innovators. This focus underlines a perennial concern for small New England states — incentivizing talented graduates to start their businesses in the same states as their alma maters. She has pledged, if elected, to create the Rhode Island Innovation Institute to “tak[e] the good ideas coming out of our colleges and universities and [turn] them into products that we make right here in Rhode Island,” as well as to begin a concierge service to “help small businesses navigate state and federal regulations, and connect them with the resources they’ll need to thrive.” Though Raimondo hasn’t made her tax policies quite as clear as Fung has, she has said that she opposes higher taxes across the board, claiming that the issue isn’t insufficient revenue, but budgetary focus.

“[Rhode Island has] the money,” she said, “we just don’t spend it wisely.” She criticized her primary opponent and current Providence mayor, Angel Taveras, for property tax increases he instituted earlier this year. Raimondo instead plans to fund increased infrastructure investment through low-interest loan programs. To round off her platform, she has also pledged to increase Rhode Island’s minimum wage from $8 to $10.10 — a move that Fung has opposed, saying that it would damage the state’s economy.

Fixing the business climate through various entrepreneurial incentives is the common thread in both candidates’ economic policies. While their approaches are different — Raimondo wants to use the government as an aid, whereas Fung wants to minimize its influence — the focus is the same. In this way, Rhode Islanders’ general frustrations are reflected in the gubernatorial election: People want jobs and need renewed hope in their state. Attracting energized businesses will combat the post-recession status quo from both fronts.

Did Someone Mention Pensions?

The 800-pound gorilla in the race that threatens to trample both candidates is pension reform. Until recently, Rhode Island faced $8.9 billion in unfunded pension liabilities. Such liabilities force governments to fund the salaries of retired workers through current tax revenue rather than previously accrued savings. With such a sizable chunk of the state’s income at risk, Rhode Island feared going the way of Detroit, which declared bankruptcy after being unable to fund its $3.5 billion dollar pension shortfall. In Rhode Island, the gap in funding threatened to crowd out public sector spending for education, public works and the police department. An inability to pay pensions would have left the future of Rhode Island’s 66,000 state workers, and the underfunded public programs they staff, hanging in the balance. As the general treasurer of Rhode Island, Raimondo found herself in an essential position to resolve this crisis.

Raimondo’s plan, which was passed by the legislature in 2011, faced opposition from labor unions until a temporary agreement was reached last year under her tenure. The new agreement leaves the state’s liability at $5 billion, slightly higher than the $4.8 billion figure stipulated in the original legislative overhaul. However, this still decreases the total liability by $3.9 billion. The compromise kept many core aspects of the temporary plan but lightened the load on state workers closer to retirement, essentially softening the burden for workers with seniority. Raimondo took what her supporters dubbed a progressive approach towards the state’s pension reform. In her “Truth in Numbers” report, she expressed concern for the impending pension crisis, emphasizing that it could have led to insufficient funds for other crucial social services. Before the settlement, Raimondo’s pension overhaul curtailed benefits, increased employee contribution to individual retirement accounts, raised the retirement age of public sector workers from 62 to 67 and provided cost-of-living adjustments to retirees every five years until pensions were 80 percent funded. This design remained largely intact during last year’s changes. Unsurprisingly, her plan has garnered stark opposition from public employee unions. Although a 2011 Brown University poll found that 60 percent of Rhode Islanders supported Raimondo’s pension reform, her plan has since generated uproar in both liberal and conservative wings of the state. In combating these critics, Raimondo has suggested that her approach towards pension reform is a pragmatic “national model” that other states with pension struggles could follow.

Many Democrats remained unconvinced. In addition to union dissenters, progressives have questioned Raimondo’s choice to invest Rhode Island’s pensions on Wall Street. As treasurer, Raimondo created the Ocean State Investment Pool, designed to help the state and its municipalities receive better returns on their investments by trusting private firms with the funds. But doing so cost the state a considerable amount of money: Around 15 percent, or $1 billion, of the state fund was handed to Wall Street hedge funds, who take 20 percent performance fees out of any profits. This plan, along with Raimondo’s heavy fundraising pulls from investment firms and her history in venture capital, led Forbes magazine to call her the “handmaiden” of Wall Street firms.

Fung has capitalized on this disenchantment with Raimondo’s Wall Street connections to further question her credibility as an economic leader. In a 2014 editorial piece for the Providence Journal, Fung called Raimondo’s pension overhaul “simply outrageous” and stated that representatives must move beyond “closed-door, behind the scenes deal[s].” Fung argued that the plan would create unnecessary fees for taxpayers at a cost of over $10 million for Rhode Island’s cities and towns. But despite Fung’s objections to Raimondo’s pension reform plan, he instituted a similar plan in Cranston in February 2014, though his is less austere and leaves more of the city’s liabilities unfunded. However, there are fundamental similarities: Fung’s plan also limits cost-of-living adjustments and, while it will immediately save Cranston’s taxpayers about $6 million, it has similarly been met with opposition by some of the city’s retirees, who are now suing the city in the Rhode Island Superior Court. Fung also had a hand in crafting the statewide pension reform plan spearheaded by Raimondo. In 2011, he was an advisory group participant on the reform panel.

Despite criticism on multiple fronts, Raimondo has not backed down from her approach, which she says will “produce strong long-term returns while reducing risk and ensur[ing] retirement security.” She notes that the new investments are only halfway through their life cycle and that it will be a few years until the state fund sees a positive return. And even though Raimondo initially drew the ire of organized labor, nearly all the unions that opposed her in the primary have now fallen in line with the Democratic candidate. Nevertheless, the battle is far from over. For Raimondo’s supporters, her pension reform plan is the strongest example of her ability to deal with the state’s still fledgling economy; for her opponents, it’s an example of her strong ties to Wall Street interests. While Fung’s role in the statewide pension reform plan has received less attention than Raimondo’s, it highlights how similar the two really are when it comes to Rhode Island’s pension problem. No matter who wins, it looks unlikely that unions and soon-to-be retirees will have a close ally in the statehouse.

This, That and the Other:

With Rhode Islanders clamoring to get the economy back on track, Raimondo and Fung have largely steered clear of contentious disputes over social issues and education policy. But this doesn’t mean they are on the same page. The Rhode Island Right to Life Committee and the National Rifle Association (NRA) have both endorsed Fung, while Planned Parenthood has endorsed Raimondo. Though Fung is far from extreme on either issue, he has made a noticeable effort to downplay issues like the environment, gender politics and gun control. Some have gone so far as to question his pro-life endorsement, since he referred to himself as pro-choice at the first Republican debate in June of this year. When it comes to gun control, Fung has noticeably changed his stance; in 2004 he voted in support of a nonbinding Cranston City Council resolution to ban assault rifles, but he now boasts a 93 percent pro-gun rating from the NRA.

Raimondo, on the other hand, has emphasized social issues in her campaign, in part because of her potential to become the first female governor. She has touted her Planned Parenthood endorsement and has policy proposals for pay equity and environmental issues prominently displayed in her online literature. She has also expressed her desire to enact stricter gun-control laws.

The future of Rhode Island’s schools and universities is another place where these candidates differ. Raimondo’s views on college education fall squarely in line with the Democratic platform — subsidize higher education to promote a stronger middle class and a more fortified economy. She is running on an election mandate that includes a loan forgiveness program, scholarships for in-state colleges and partnerships between community college training programs and employers. This palette of policies dovetails nicely with Rhode Islanders’ desire to extend their state’s appeal past the undergraduate years. And Raimondo’s plans dig deeper than post-graduate education. If elected, she has promised to rebuild physically crumbling schools, provide expanded options for extracurricular activities and improve teacher resources. Her campaign estimates that by 2018, 61 percent of all jobs will require a post-secondary education. Consequently, her propositions echo the need for funding that can provide schools with the resources to teach children the skills necessary for college and the workforce.

Fung’s education policy, however, focuses on increased accountability in the state’s educational structure. Fung, like Raimondo, posits that education must be “innovative and accountable” in order to prepare children for their future careers and argues that a more educated workforce will innately bring about economic development for Rhode Island. But Fung also has a highly specific vision that begins with leadership at the top. To these ends, he has proposed creating an Education Cabinet with newly separated boards for K-12 and higher education, which would work closely with the governor’s office. In addition, his campaign has promised to help the University of Rhode Island (URI), the state’s flagship university, establish a Board of Trustees or Regents. Through these efforts, Fung hopes to “eventually reduce the University’s reliance on state funding.” That funding currently covers 12 percent of URI’s $524 million operating budget — a total of $65 million.

Following the pattern of being different, but not too different, Raimondo and Fung agree on many specific issues pertaining to education policy. When asked about current teacher evaluation policy, Raimondo showed support, stating that “teachers should be given regular feedback and coaching,” while Fung expressed his disappointment in the elimination of many annual evaluations for education. Both candidates concur that a mandatory standardized test for high school graduation would add intrinsic value to receiving a diploma. Additionally, they have both supported charter schools, albeit for different reasons. Raimondo’s argument focuses more on equal funding for all educational ventures, while Fung strongly believes that charter schools can serve as models of innovation for new and improved curricula. On Common Core, Raimondo has stated her belief that it will “make our state more competitive in a global economy,” and Fung also has offered his support — though with the caveat that it must provide enough flexibility for teachers in the classroom.

Big Changes for a Tiny State:

It remains to be seen whether a new ethnic or gender identity in the governor’s office will bring new politics with it. Jumpstarting a lagging economy will be the central mandate of whoever is elected, but there are many other profound issues that plague the smallest state in the union. Raimondo has laid out a detailed plan that includes raising the minimum wage, funding infrastructure projects and providing resources for entrepreneurs. Fung’s plan sticks to common conservative principles for stimulating economic growth — tax cuts and bureaucratic trimming — fused with a focus on education and good governance. Compared to the vicious polarization of national politics, Rhode Island’s race for governor offers a relatively insightful centrism. The small state has a long way to go before achieving economic prosperity, but the big vision of a centrist in the governor’s mansion will help steer it towards success.