By David Chy

“Brown University’s long silence can only be considered our approval,” student leaders cried. This sentiment was widely held on campus by those who believed that the University could not ignore the controversy of the Vietnam War. Students felt that by hiding behind a veil of neutrality, Brown was complicit in what many labeled an unjust war. While Brown students have long had a liberal reputation, more surprising is how clearly this attitude was mirrored in other factions of the university — members of both the faculty and administration lent their voices to student activists’ attitudes on the matter.

Early signs of student opposition to the Vietnam War can be traced to a campus-wide effort to eliminate the University’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program. Though highly popular throughout much of the 1950s and 1960s, Brown’s ROTC units faced increasing hostility as violence escalated in Vietnam, peaking in 1967 when 35 members of the Brown Committee to Abolish ROTC picketed the program’s annual spring review in Meehan Auditorium. In November of that same year, both the student government and the Brown chapter of the American Association of University Professors declared the mission of ROTC to be incompatible with that of the University. By the end of the spring semester, the faculty had voted to phase the program out entirely over the next four years, bringing the matter to a definitive conclusion and underlining the distinctly pacifist mood on campus.

Antiwar activism continued to gain traction at the turn of the decade. In October 1969, objection to the war ascended as high as the office of the college president. Acting President Merton P. Stoltz joined 78 other college presidents to publically urge President Richard Nixon and Congress for a “stepped-up timetable for withdrawal from Vietnam.” The following spring semester, over 120 students staged a sit-in at the University’s career placement office, barring an US Navy recruiter from entering the premises. The students’ passion was so strong that, as Dean William Brown recorded the names of the offending students, protestors who arrived late requested that their own names be added to the disciplinary list as well. “By allowing the military to recruit at Brown, the university is making a complicit statement about US foreign policy,” wrote the Brown Daily Herald’s Editorial Board, reflecting the fervor of the student body. “The university is actively participating in the war effort by aiding the armed forces to enlist soldiers and officers from the Brown community.”

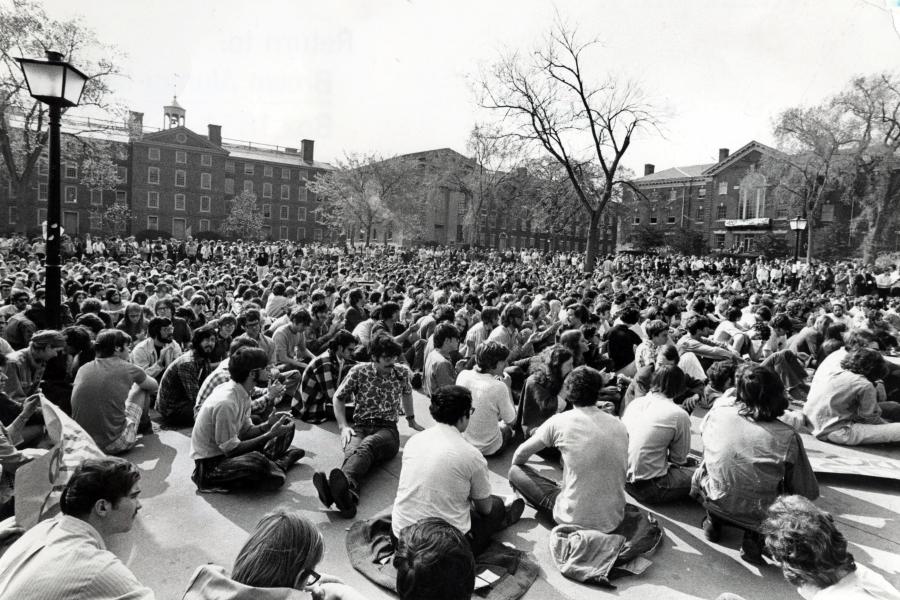

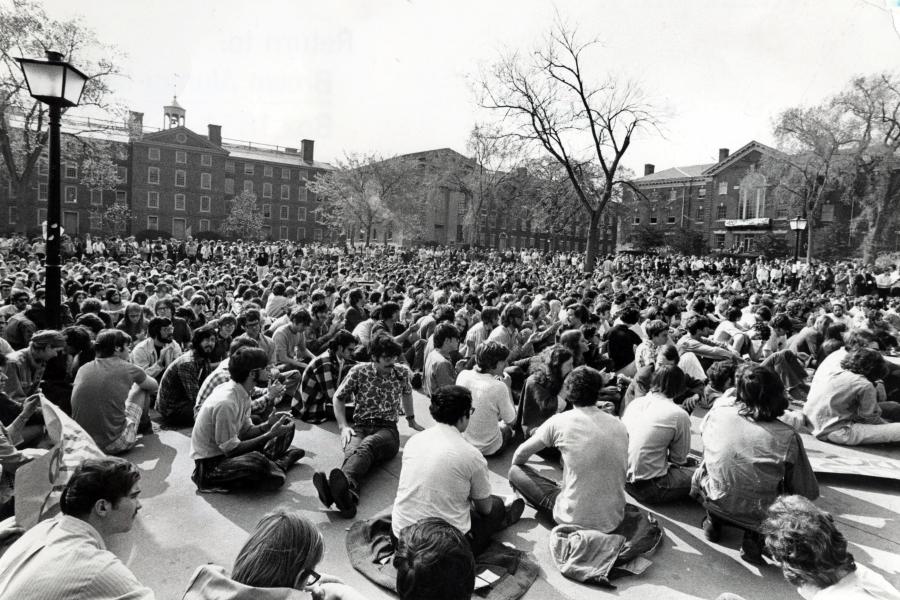

The campus fiercely organized after the announcement of Nixon’s ordered invasion of Cambodia and after the fatal shootings of four student protesters at Kent State University. On May 4, 1970, thousands of Brown students amassed on the Main Green and decided to strike by a vote of 1895 to 884. The next day, faculty took steps to support the strikers and declared “all finals and papers optional.”A series of May teach-ins at Wilson Hall sought to educate the Brown community about higher education’s complicity in the Vietnam War, citing ROTC, accommodations for military recruiters and investments in the defense industry.

Brown’s 1970 Commencement observed further developments in the war protest. The University’s usual graduation ceremonies were vastly scaled back, with the focus instead switching to parental and alumni education. Additionally, with administrational approval, seniors and alumni groups replaced the traditional ROTC honor guard in the procession. As Daniel Cummings of the Brown Daily Herald noted, “For the first time since the Revolutionary War…the university suspended classes over a political issue, the nationwide strike against war and repression.” The University’s presentation of such a united front on one issue was, as Cummings noted, an epochal moment in Brown’s history. From the vantage point of 40 years onward, the legitimacy of the Vietnam War can be long debated. But it is undeniable that, on Brown’s campus, there was a consensus the strength of which has been seldom seen since.