I’m thankful for America. Does this mean I believe in American exceptionalism? It’s a question I’ve sometimes asked myself. For conservatives, American exceptionalism is a given, founded on America’s history of independence and freedom. For liberals, exceptionalism is often a dirty word that seeks to obscure America’s many sins and failings. Conservatives interpret this as a liberal disdain for America, when often it’s based on a progressive desire to correct our society’s faults.

If by American exceptionalism we mean America is better than the rest of the world, that’s a sentiment so vague and lacking in criteria as to have no meaning. If exceptionalism means our history is faultless, then the genocide of Native Americans that is an implicit part of this very holiday disprove that idea. But if exceptionalism means that America has unique and sometimes extraordinary aspects of its history and character, then there is truth to American exceptionalism.

America was different from most of the world at its inception because of the lack of a permanent aristocracy, which helped increase social mobility. Literacy was unusually high, at least among white men. Historians like Bernard Bailyn argue that pamphlets provided the ideological fuel for the American Revolution, which supports the idea that high literacy rates played a key role in the nation’s founding.

Bailyn’s disciple, Brown Professor Emeritus Gordon Wood (famously name-dropped by Will Hunting), argues that what sets America apart is that the nation was founded, and remains bound together, by a set of ideas. Most other nations have a deep well of history, myth, fairy tales, language, and other elements of culture that frequently become fodder for nationalism. America is young, and our founding myths are about real men espousing a set of beliefs and ideals.

The criticism of Professor Wood goes to the heart of the problem with American exceptionalism. Wood downplays class distinctions and emphasizes rhetoric – while the people spouting that rhetoric were all slave-owning white men. Early America may have been more socially mobile than other countries, but there’s always been a class system in America even without an aristocracy. Literacy rates were high, but only for white men. How can we even discuss the positive contributions of America without being drowned in the negatives?

Occasionally we need to step back and acknowledge some of the American traits that, when viewed alongside the arc of human history, are exceptional. Democracy, when it was adopted in the form of a republic by the Founding Fathers, was truly radical. There were doubts that democracy would succeed, but now it’s the ideal that many oppressed peoples strive for. Despite notable examples to the contrary, we live in an extraordinarily peaceful nation. The thousands of years of human history are full of routine violence at a level now unthinkable, at least inside this country. And our citizens have a remarkable respect for the rule of law. For example, one way to quantify tax evasion is to measure the “shadow economy” – economic activity that is legal but off the books. In Greece, that shadow economy is about 27.5 percent of GDP, while in supposedly anti-government, anti-tax America that number is only 9 percent.Critics will argue that these rosy statements overshadow so many faults with our country – the injection of corporate money in the democratic process, the violence the US inflicts on other nations with its military, and the unfair application of the law to minorities, to name a few. All these are important issues. But if we don’t stop, even for one moment, to reflect on what America has done right, we risk losing perspective and forgetting what core ideals we should be protecting and nurturing.

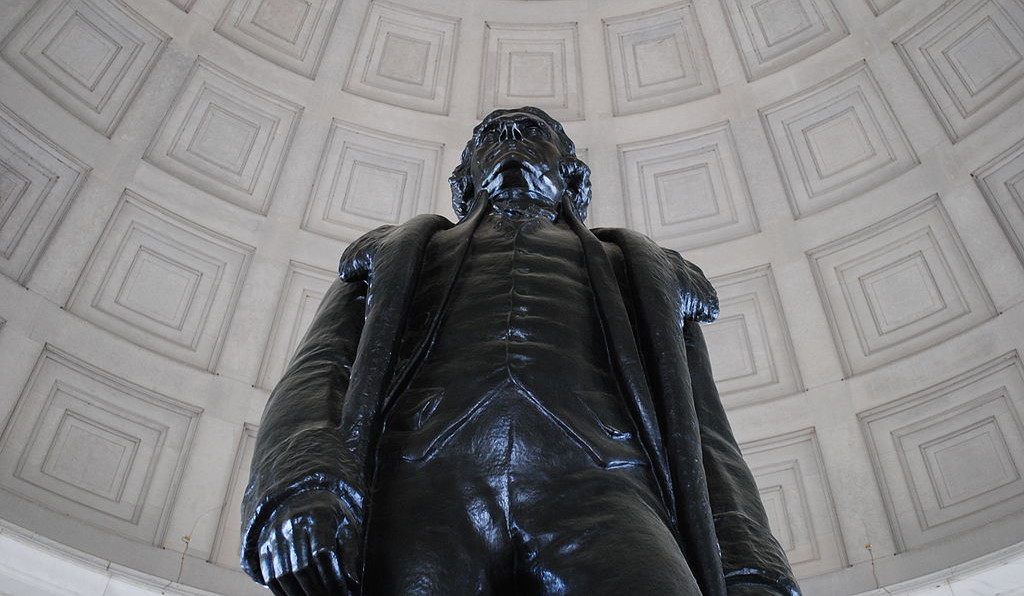

The greatest moment of America history may have been on March 4, 1801, when Thomas Jefferson took over the presidency from John Adams. Jefferson had won a bitter campaign that was decided in the House of Representatives when no candidate was able to gain a majority in the Electoral College. When Jefferson took office, power passed from the Federalist Party of Adams to the Democratic-Republican Party of Jefferson. Despite the rancor of the election and the messiness of the electoral process, there was no revolt or coup or bloodshed. Power transitioned peacefully. We take this for granted now, but changes in regime were often bloody affairs for much of world history. Maybe Thanksgiving isn’t the best time to emphasize these exceptional facets of American history and of the American character. But I think it’s as good a time as any. So doing my best to recognize my own privilege and this country’s many faults, I maintain that I’m thankful for America.

Matt, you’ve taken these words right outta my mind and onto the page. Great article; please keep writing more!!

Nicely stated, Matthew. It’s important to keep the baby while disposing of the dirty bathwater. Too often we forget this in the name of progress. Thanks for reminding us. Happy Thanksgiving!