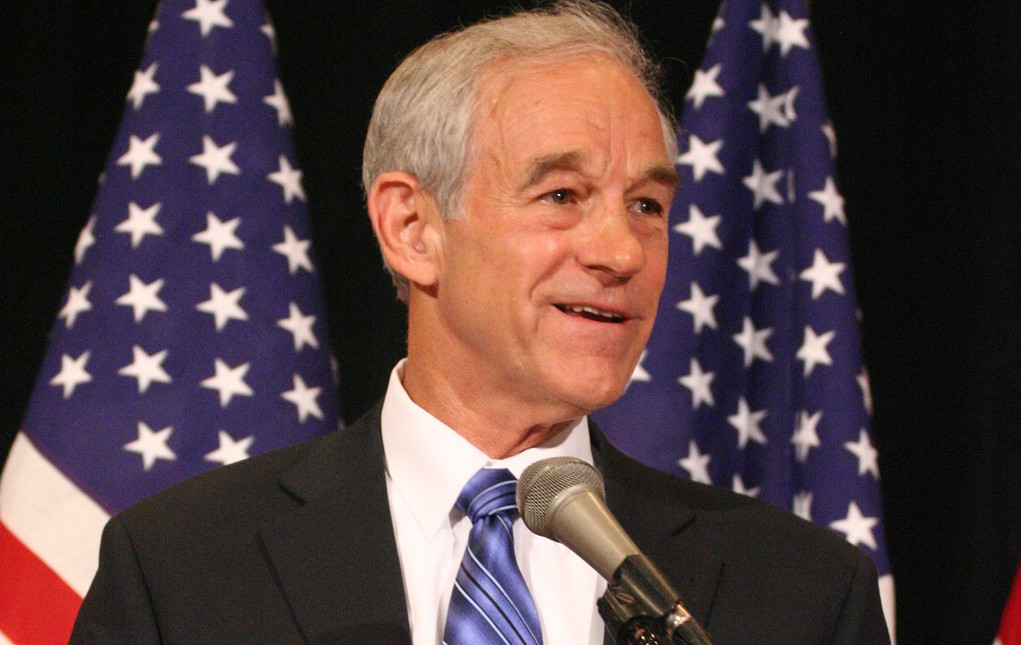

Ron Paul is a physician and former U.S. Representative for the 14th and 22nd congressional districts of Texas. Dr. Paul ran for President as the Libertarian Party candidate in 1988 and as a Republican primary candidate in 2008 and 2012. In 2013 Paul launched the Ron Paul Institute for Peace and Prosperity, which seeks to expand advocacy for noninterventionist foreign policy and the protection of civil liberties in the US. Paul spoke with BPR’s Henry Knight.

Brown Political Review: I want to talk about foreign policy and noninterventionism. You voted against the PATRIOT Act in 2001, and oppose the use of torture in military interrogations. What should the U.S. do about Guantánamo Bay? Are civilian trials a viable option?

Ron Paul: We should follow the Constitution. It doesn’t authorize us to set up special tribunals on our land to avoid these civilian courts, so I would say [detainees] should all be tried in civilian courts. The question comes up, “Yeah, but what about this war we’re in? What about these enemy combatants?” That’s where the trouble comes, because there is no declared war, there is no clear definition of an enemy combatant — it’s arbitrary and set by a few people in the [presidential] administration.

So my position has been to close Guantánamo, and some people say, “But what about these bad guys that we find around the world?” We’re not supposed to be the policeman of the world, and if we had a noninterventionist foreign policy, there would be very few who are deliberately trying to kill us, either here or overseas. So we create this problem. I think that Guantánamo and the abuse of civil liberties are closely related to our foreign policy. [There are] consequences for foreign policy that oversteps the bounds of what we should be doing.

BPR: What do you make of President Obama’s “red line” policy in Syria? If the Assad regime used chemical weapons, does the U.S. have an obligation to intervene? Or was the red line policy a misstep in the first place?

Paul: Both. It was a misstep in the first place, and he shouldn’t have intervened, even if they claimed they’re finding something. But I think the big question is why should anybody believe what they tell us? How many men and women lost their lives — how many dollars have we spent — because the Bush Administration deceived us into believing Saddam [Hussein] was about to attack us, that he had nuclear weapons, used poison gases and was about to attack us? Look at what we got ourselves into, by false information. So I would say once again that this should all be avoided.

I think there’s a major problem in Syria, and that we shouldn’t be involved. We’ve already been very much involved in the rebel groups, and very closely aligned to the rebel groups is the al-Qaida and the al-Qaida in Iraq—there was no al-Qaida [there] before, now there is. So we prop up dictators, then we turn on them, then we throw them out and then we put somebody else in who’s actually worse. That could be the case in Egypt. We messed around in Libya; it hasn’t helped. It’s actually militarizing and radicalizing the Middle East. I think it’s a great danger to Israel, too, because we bought friendship over the years, paid a lot of money, and then all of a sudden we decided we’d throw out all these dictators—Saddam Hussein was an example, Mubarak was an example and we were on-again, off-again with [Moammar] Gadhafi. Noninterventionist foreign policy offers so much because we’re broke. It really has to be considered seriously.

BPR: How do you think the U.S. should respond to threats from the Kim Jong-un regime, and at what point does North Korea become enough of a legitimate threat to the safety of U.S. citizens to justify retaliation?

Paul: Well, if our security was threatened, and he was actually able to do something to us, we’d have to consider it. But compared to what? The Soviets had 30,000 intercontinental ballistic missiles in Cuba, and yet we never had to fight them — we just contained them — and we won the Cold War, the Soviets lost for economic reasons. The North Koreans have already lost for economic reasons, they can’t even feed themselves, they can’t even turn lights on, they don’t have paved highways. For us to be intimidated into doing stupid things is [something] I don’t understand. Why we should be so easily pushed around like that to do these things that satisfy some special interests? For example, the military-industrial complex loves this because more weapons are going to be built. They’re talking about billions and billions more dollars to be spent on defensive detection and retaliation in the Far East because of North Korea, and that’s all just propaganda. If we hadn’t been in Korea for all these years and had gotten our troops out of there, I believe that the Peninsula would be unified, just like North and South Vietnam became unified after we left, under very, very, dire circumstances. But [Vietnam] became more Westernized, more peaceful and more friendly once we gave up on our militarism.

BPR: I’d like to turn to abortion policy now. You believe that life begins at conception, correct?

Paul: Well, I don’t [just] believe it, that’s what everyone agrees to. That’s science. When else would life start? There’s no other choice. Everybody knows when it starts…The big question, of course, is the dire circumstances of unwanted pregnancies, and how do you balance that out with whether [abortion is] perceived as a women’s right. I think that the only way people can see clarity is to take a look at an ultrasound in the seventh, eighth or ninth month, when there’s a fetus that weighs 4, 5 or 6 pounds, swallowing and sucking his thumb, and to say, well, to throw that life away, means nothing. The case [of Dr. Kermit Gosnell] in Philadelphia—a doctor is being tried for murder because he delivered, the fetus would still be alive, he was meant to abort the fetus, so he would kill the fetus afterward.

BPR: How do you respond to people on the left who have said that the reason that the Gosnell abortion clinic occurred—the reason this man was able to perform illegal, [late-term] abortions on these women—was because abortion isn’t publicly funded, and because it isn’t publicly funded, low-income women have to save in order to afford an abortion, and they can’t afford it until the seventh, eighth, ninth month of their pregnancy. And they’re forced to turn to someone like Gosnell, who takes advantage of their low-income status and performs these late-term procedures.

Paul: That has to come from an authoritarian who claims they know what’s best for everyone, and that they can use government force to do it, to extract money from one group and give it to another to avoid this. [It] is almost like saying, “We don’t want violence when someone robs a bank, so why don’t we just let them go in and take the money?” and [have] a government agent help them and use some method of redistributing wealth by handing out the money to them. No…what they should ask is, “I thought [legalizing] abortion was supposed to get rid of these abortion mills and these back-alley abortions, and yet with all the legalization, we [still have this] back-alley abortionist?” — who killed a woman, too. A woman died in this, as well as the fetuses.

BPR: Don’t you think that the situation is at least partially attributable to the fact that low-income women don’t have the money to afford an abortion, and so they save until they can, and by that point their only option is a back-alley abortion or some illegitimate or illegal procedure?

Paul: Hardly. I really don’t believe in it. If it were true I would say that’s not a justification to take money from people who detest abortion and give it to people to [carry out] abortion. So I think one of the most foolish things that the left did and does on the abortion issue is to extract funds…through taxation from people who have deeply held moral reasons for why they think it’s wrong, and give the funds to other people to [carry out abortions]. That, I think, has incited the right-to-life movement more than anything else. So I think it’s a foolish political stunt to make someone who is devoutly opposed to something and then make them pay for it.

BPR: You’ve said that abortions should be a states’ rights issue, and that life begins at conception. But if life begins at conception, then does a fertilized egg in any form becomes a constitutionally recognized person with the right to equal protection under the law? Wouldn’t that effectively nix abortion as a states’ rights issue?

Paul: I wasn’t so broad in the statement as to say that all fertilized eggs are deserving of the same protection. I’m saying that this is very difficult and that the states have to sort it out because there are going to be a lot of different circumstances. I, as a right-to-life doctor, had to do a so-called extraction of a live fetus — that would be an ectopic pregnancy. The pregnancy was there, and there was no other way to save the woman’s life and there was no way you could save the fetus’s life. So those are mitigating circumstances that have to be sorted out. But to have one national law that would come down and make this decision…If a woman has a miscarriage, the fetus may still be alive, but if it’s not much more than a fertilized ovum, it can’t have the same protection as [a fetus] in the third trimester. [This issue] is difficult, [and] that’s the reason you go to local officials to sort it out. Just think of how many different penalties we have for murder — first, second, third-degree — and manslaughter. [For] all these different things, the penalties are different, and that’s why it’s not easy to come up with a single solution.

BPR: Your son [Rand Paul] has recently garnered a lot of publicity for his potential presidential candidacy in 2016. What advice you would give to Rand if he were on the ballot next election cycle?

Paul: I wouldn’t give him any advice; he’s on his own. He makes his own decisions. I haven’t really addressed that subject at all.

BPR: What is the area of most political disagreement between you and your son? Do you generally agree on most issues? Are there issues you don’t necessarily agree on?

Paul: We essentially agree on all the major issues.

BPR: In the wake of the 2012 presidential election, Republicans appear to be searching for answers to offset some of the electoral disparities that existed in minority demographics. As Republicans try to appeal to those demographics, do you think there’s a new niche to fill in the party? Can Libertarianism fill that niche?

Paul: All I know is that the Freedom Philosophy, the protection of an individual not because they belong to a group—they don’t get rights because they belong to a group—should have an appeal across the board. This should bring people together. If people understand that liberty is important and you get to use it any way you want, as long as you don’t hurt other people, that should bring us together as much as possible, as much as anything else. This whole idea that you have to provide special benefits to certain groups and try to appeal in that manner, which has been done and demagogued for years, is wrong. It’s very divisive, and it encourages excessive spending, the whole works. Liberty has to be defined. Liberty has to be understood, and it becomes irrelevant whether you belong to a majority class or minority class, because the minority I want to protect is the individual. The individual should be seen as the person who has the rights, and not because anybody belongs to a certain group.

BPR: In your book “End the Fed” you wrote that you oppose increasing the money supply and government spending. So when we’re in a recession or economic downturn, how would you propose we get out of it?

Paul: Get out of the way as soon as possible. [The government] spends too much and prints too much, and you have to understand the business cycle on how fixing prices and fixing interests rates creates malinvestment [sic], distortions and excessive debt. So if you don’t correct the problem, if you don’t allow the correction which markets are demanding, it will take you a long, long time to get out of it. That’s why we were in a depression for fifteen years. That’s why Japan has been in a deep recession for a couple of decades. That’s why we’ve been in this horrendous recession now. If people were honest with themselves, they would say that all that spending, and all that inflating of the currency has done nothing more than enrich the already-rich, and enrich the banks and the military industrial complex. And it has, actually—what is so ironic is that if you look at the poor and at middle -class average and at minorities since Obama’s been president, their standard of living as gone down, and that’s what people have to look at. Spending is nothing more than interference in the market — it’s taking from one and giving to another, and destroys incentives and destroys production. We’ve been up and down, and patched these things up over for 50 to60 years, but it doesn’t work anymore. The question you ask would have been a little more difficult to answer 10, 15, 20 years ago, even though I would have believed the same thing. But the climax is here—now it doesn’t work. [The government] can create trillions and trillions of dollars, and about all that you see is a little bit of uptick in the stock market. But there’s no real economic growth [or improvement in] the standard of living. The rule is that if you destroy a currency, the middle class sinks, the poor get poorer and the rich get richer — in spite of all the rhetoric from the do-good liberals, who say we’re going to take care of the poor when all they do is take care of the welfare of the rich. [This is the case] for both parties.

BPR: U.S. v. Windsor, the case about the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), will be ruled upon in the coming months. You have said that you’d rather government play little if any role in marriage. But the federal grants benefits based on marital recognition—with Edie Windsor, she wants an estate tax cut. What is more antithetical to libertarian philosophy: the federal government defining marriage, or the federal government distributing benefits for that marriage?

Paul: I don’t want the government to be involved in defining couples, and that would go a long way. The libertarian is trapped on a question like this, because we don’t believe in the welfare state. So when you’re asked, “Well, would you allow welfare to be passed out to all spouses?” and therefore expand the welfare state, then they turn around and say, “Oh, you’re not really for making their own choices.” So [the issue] becomes very, very difficult. My answer is that the government should be out of welfare — but they’re not going to be out of welfare soon. The only way I think you could do this, to halfway come close to the ideas of liberty, is to allow people to name their beneficiaries. But the whole idea that the federal government tells a local husband who can come into a room to visit — that really annoys me to no end. Why can’t the individual just go in and the patient say, “Look, my friend wants to see me, let him come in”? If you could name the beneficiary, then you don’t have to ask what your relationship is to them. But I want the government out of the business of marriage. I don’t know why we have to get a license to get married.

BPR: In that sense, do you think some aspects of DOMA are problematic?

Paul: I wasn’t there when they voted on it, but my main objection was that it was — more or less — it’s back to how do you solve the very difficult problem of abortion, where some things need to be sorted out at the local level…if there is anything to be done it has to be done at the local level, and I think DOMA tried to prevent the federal government from taking over.

RT @BrownBPR: BPR Interview: Ron Paul: BPR’s Henry Knight spoke with Ron Paul, a physician and former po… http://t.co/KjFcueajlo

“The libertarian is trapped…” @RonPaul’s fascinating take on gay marriage benefits. See more from @BrownBPR http://t.co/91ozBhUoAq

“The libertarian is trapped on a question like this…” Ron Paul, in response to BPR’s question on gay marriage. http://t.co/91ozBhUoAq

RT @j3669: BPR Interview: Ron Paul | Brown Political Review http://t.co/vPb42ufLH7

#tcot #teaparty #tlot #p2 #ronpaul

RT @ElenaSaltzman: @BrownBPR has a fascinating conversation on personal liberty and abortion with @RonPaul http://t.co/W6GiaS0uT5

RT @ElenaSaltzman: @BrownBPR has a fascinating conversation on personal liberty and abortion with @RonPaul http://t.co/W6GiaS0uT5

RT @ElenaSaltzman: @BrownBPR has a fascinating conversation on personal liberty and abortion with @RonPaul http://t.co/W6GiaS0uT5

@BrownBPR has a fascinating conversation on personal liberty and abortion with @RonPaul http://t.co/W6GiaS0uT5

RT @BrownBPR: BPR Interview: Ron Paul: BPR’s Henry Knight spoke with Ron Paul, a physician and former po… http://t.co/KjFcueajlo