As the U.S. Supreme Court considers two prominent cases with monumental implications for same-sex marriage, legislatures in several states including Rhode Island have taken up debate whether to potentially preempt the Court by ending their own same-sex marriage prohibitions. Currently, nine states plus the District of Columbia explicitly perform and recognize same-sex marriage. The majority of states prohibit it through statute or constitutional amendment, while a handful grant limited rights, including civil unions, that fall short of full marriage.

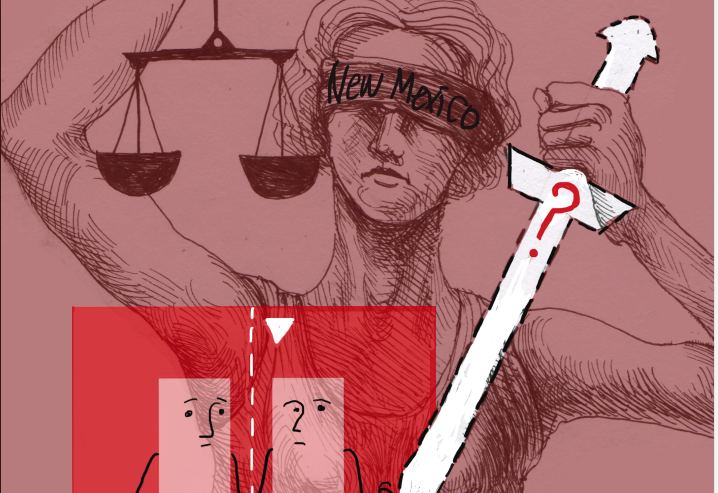

In New Mexico, however, a very different and unusual controversy over the legality of gay nuptials is unfolding. There the question is not whether same-sex marriage should be legal in the state, but whether it already is. And the truth is, no one really knows the answer.

New Mexico is the only state in America whose marriage laws neither overtly allow nor prohibit same-sex marriage. In fact, they do not reference same-sex relationships. On the basis of this ambiguity, Santa Fe Mayor David Coss and City Attorney Geno Zamora have recently called on the state to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples. On March 27, they introduced a resolution in the city council calling on county clerks to recognize “that same-sex marriage is legal in New Mexico” and “to follow state law and issue marriage licenses to loving, committed couples who have the right to marry the person that they love, including same-sex couples.”

New Mexico Statutes §40-1-1 reads, “Marriage is contemplated by the law as a civil contract, for which the consent of the contracting parties, capable in law of contracting, is essential.” Notably, this statute does not require the parties to marriage be one man and one woman; in fact, it makes no reference to the genders of the contracting parties whatsoever. Meanwhile, §40-1-9, which enumerates prohibited forms of marriage under state law, does not forbid same-sex marriages. A reasonable inference from these facts — based on the principle that acts are generally permissible if they are not specifically forbidden — is that same-sex marriage is already legal in New Mexico.

Indeed, the rush on the parts of states such as Ohio and Hawaii to explicitly prohibit same-sex marriage supports the argument that same-sex marriages are permitted absent a specific legal prohibition. After all, if this were not the case, why would those states feel the need to proactively ban same-sex marriage at all?

Inquiry into the legal status of same-sex marriage first arose in New Mexico on February 20, 2004, when Sandoval County Clerk Victoria Dunlap began issuing marriage licenses to gay couples. As Dunlap told the Albuquerque Journal, her decision came after consultation with the county attorney who said that state law on the subject was ambiguous: “This has nothing to do with politics or morals,” she said. “If there are no legal grounds that say this should be prohibited, I can’t withhold it.” Dunlap’s same-sex marriage license-issuing spree lasted for all of eight hours. Prompted by an inquiry from state Senator Timothy Jennings (D-Roswell), then-New Mexico Attorney General Patricia Madrid issued an advisory opinion by the end of the day asserting that New Mexico state law did not permit same-sex marriage and that the licenses were “invalid under current law.”

Madrid’s reasoning rested on the fact that several state statutes appeared to “contemplate that marriage will be between a man and a woman,” noting that the official marriage application form adopted by the legislature “requires a male and a female applicant,” that the “rights of married persons are set forth as applicable to a husband and a wife,” and that “property rights of married persons are expressed as existing between a husband and a wife.” Furthermore, Madrid cited a decision by the New Mexico Supreme Court establishing that evidentiary privilege between spouses is “limited to communications that occur while the parties are a husband and a wife.” Drawing on traditional definitions of “husband” and “wife” provided by the Sixth Edition of Black’s Law Library, Madrid concluded that marriage in New Mexico is limited to a man and a woman.

Dunlap stopped issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples after Madrid released the advisory, and New Mexico officials and agencies have operated under the directive since 2004. Though a series of lawsuits over the issuing of same-sex marriage licenses ensued, the matter was never litigated to its conclusion, as the suits were dismissed before a court could consider them. Given that Madrid’s letter is more or less the only public legal authority clearly prohibiting same sex marriage, it is worth noting several important caveats with respect to it.

The ambivalence in Madrid’s tone that permeates the letter is unmistakable. She explicitly declines to issue a formal opinion, instead offering a more informal advisory letter, and acknowledges the likelihood that a prohibition of same-sex marriage could be declared unconstitutional in the courts. She cites Lawrence v. Texas (2003), the Supreme Court case striking down anti-sodomy laws nationwide, and Goodridge v. Department of Public Health (2003), the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court case that paved the way for same-sex marriage in that state.

More important is the indubitable fact that neither state courts nor state agencies are bound by the opinions of state attorneys general. “An AG opinion is just as the name suggests, an ‘opinion’ on the law,” says Stephen R. McAllister, the solicitor general of Kansas and a professor of law at the University of Kansas School of Law. McAllister notes that while executive officials are likely to follow an attorney general’s advisory opinion, because they lack both legal expertise and the broad authority to interpret the law that courts enjoy, they are not necessarily bound to do so legally.

As the advisory letter states, New Mexico marriage law is replete with references to husbands and wives — as is the marriage license application form, whose text was adopted by the legislature via statute. These references do not necessarily carry much significance; the word “husband” can be used in reference to a woman in a lesbian relationship, and “wife” can be used in reference to a man married to another man. While such usage may have been unthinkable by the creators of the application form in 1961, today it is far less uncommon and falls within the scope of ordinary parlance.

Other areas of New Mexico marriage law also indicate the validity of same-sex marriages. New Mexico Statutes §40-1-4 reads: “All marriages celebrated beyond the limits of this state, which are valid according to the laws of the country wherein they were celebrated or contracted, shall be likewise valid in this state, and shall have the same force as if they had been celebrated in accordance with the laws in force in this state.” In 2011 Attorney General Gary King relied on this statute in an advisory opinion holding that New Mexico is required to recognize same-sex marriages performed in out-of-state jurisdictions.

In 2010 a state judge ruled that a same-sex couple who had received a marriage license in Sandoval County, and subsequently filed for divorce, was entitled to receive divorce proceedings in court because their marriage license had been validly issued. However, she avoided the question of whether gay marriage is generally legal in New Mexico, stating only that even if Dunlap had been mistaken to issue the license, it was “not void from the inception, but merely voidable.”

Last January a bill to place a referendum on whether to legalize same-sex marriage on the ballot in 2014 was defeated in a House committee. For now, the challenge facing gay rights advocates in New Mexico may not be convincing lawmakers to make same-sex marriage legal but to convince the rest of the state that it already is.

Art by Goyo Kwon