On the evening of April 21, members of the Brown community were sent an election update from UCS President Anthony White, ostensibly reporting the outcome of the recent UCS election. Instead, what we found in our inboxes was the following piece of electoral jargon:

To reach a majority, UCS employs an Instant Run-Off Voting (IRV) system, involving the elimination of the bottom candidates and a reallocation of their votes based on each voter’s ranked preference. The race between Todd Harris ‘14.5** and Afia Kwakwa ’14 was so close, and there was a small, but significant, percentage of voters who did not rank Afia or Todd as preferences for President and thus these votes could not be reallocated to either Todd or Afia under the IRV system. For this reason, neither candidate reached the majority needed to win and the election and we will need to go into a separate run-off election between those two candidates.

For the politically inclined, the first question that may have come to mind was, “What is an instant-runoff voting (IRV) system, anyway?” More to the point, shouldn’t elections be structured so that we don’t have to vote twice?

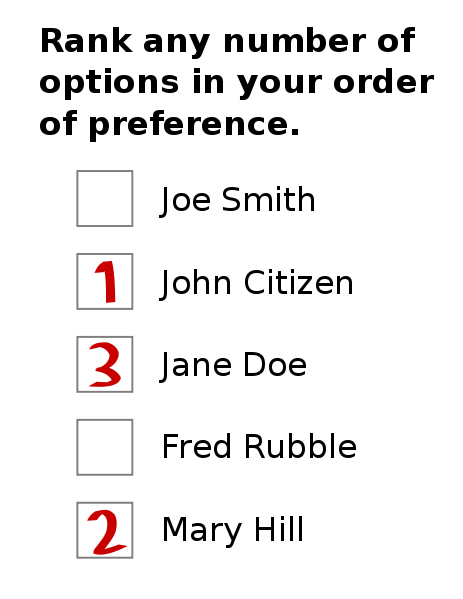

IRV or Alternative Vote (AV) is a system of voting designed to be more democratic than the current systems used in most elections both here in the United States and around the world because voters can choose more than one candidate of whom they approve. In IRV, voters rank candidates in order of preference, but they do not have to vote for candidates whom they do not support. The candidate with the fewest first-choice votes is eliminated first, and all of his or her ballots are allocated to his or her voters’ second choice. This process is repeated until either a candidate wins a majority or all of the ballots are “exhausted”—that is, even after counting the last-choice candidates on each ballot, no candidate receives a majority of the votes. This is what occurred that caused a runoff for the UCS elections. Usually, in such a scenario, another election is called or the candidate with the most votes simply wins.

IRV is not just an interesting theory: it is also already used for Australian House of Representative elections, Indian and Irish presidential elections, and several municipal elections across the United States including those in San Francisco, Minneapolis, Saint Paul and Portland, Maine. But the case of the recent UCS election is rare: Since Brown’s by-laws state that a candidate must have a majority of votes to win, an additional runoff election had to be called when many student voters failed to rank either Afia or Todd in any order of preference. It is thus only in races that are extraordinarily close or in situations where none of the candidates appeal to a majority of voters that voters must bear the burden of performing this civic double-duty. In light of these latest campus elections, it is certainly worth taking a closer look at how IRV can ameliorate many of the problems persistently plaguing the US political process.

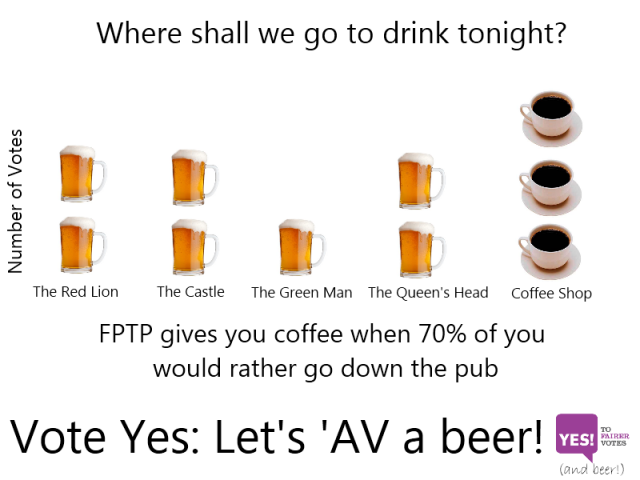

In most democratic countries, national elections employ a first past-the-post (FPTP) system of voting. The premise is simple: one vote per person, and the candidate with the most votes wins. The results, however, can be disastrous. In a proportional representation system, in which all voters vote directly for candidates and a pure plurality determines the victor, FPTP permits minority rule.

In Israel, for example, the governing coalition of Likud-Yisrael Beitenu garnered only 23.34% of the vote in this past January’s parliamentary elections. Nonetheless, Israel represents FPTP in its least flawed form. A young democracy with a still-diverse multi-party system, the political system has not yet devolved into complete two-party hegemony. Proportional representation makes the Israeli system more egalitarian for voters, but does little to build consensus since the majority of voters are unable to settle on a candidate. Though more democratic in theory, Israeli FPTP elections in practice yield a disappointing result: persistent minority rule.

In the United States, however, FPTP elections do not use direct proportional representation. Our elections are structured within several single-member districts (SMDs) in which the winner takes all of the votes. In senatorial elections, the entire state functions as one SMD. For house elections, districts are smaller, encompassing approximately 700,000 people. For presidential elections, most states are winner take-all SMDs, with the exception of a few small states that allocate their electoral votes proportionally. While FPTP elections in Israel permit multiple parties to win some seats in the Knesset, in the United States the consequences are more adverse, creating an inevitable and irrevocable two-party system in which no other parties can compete.

The two-party system arises because voters quickly realize that they must vote strategically. Candidates on the far ends of the political spectrum drop out of electoral races because they know they cannot win, and they instead search for a space within a dominant party whose platform will accommodate them. As a result, the disillusioned center becomes stuck voting not for the party with which they agree most but for that with which they disagree least. The result is a pattern in which voters flip back and forth between the two dominant parties and remain continually dissatisfied with both of them. Case in point: US Congressional approval is at an abysmal 16.5% and President Obama’s approval rating is a meager 47%. Partisan politics and contemporary chicanery certainly should take some of blame, but perhaps much of the dissatisfaction arises out of the fact that so many Americans, of whom 40% describe themselves as “independent” are denied the representation that, democratically speaking, they deserve.

The author and preeminent public intellectual Gore Vidal once penned the following description of American politics in his 1977 opus, Matters of Fact of Fiction:

There is only one party in the United States, the Property Party … and it has two right wings: Republican and Democrat. Republicans are a bit stupider, more rigid, more doctrinaire in their laissez-faire capitalism than the Democrats, who are cuter, prettier, a bit more corrupt — until recently … and more willing than the Republicans to make small adjustments when the poor, the black, the anti-imperialists get out of hand. But, essentially, there is no difference between the two parties. (268)

A similar sentiment was espoused by the recently retired Republican politician Ron Paul, the face of the modern Libertarian movement, when he came to Brown’s campus for a lecture on April 16: “People ask me if I’m in support of a third party. How about a second party?”

Under FPTP, the better an alternative to the two dominant parties performs, the greater the harm it does to its own voters. This is called the “spoiler effect,” and has most recently reared its ugly head in the 2000 presidential race, when far-left Green Party candidate Ralph Nader cost his more moderate-left opponent Al Gore the election. This was particularly horrifying because third-party voters indirectly caused the election of a candidate who lost the popular vote, as George W. Bush was able to assume the presidency with only 47% of Americans supporting him. The 1992 election was another example of third parties precipitating minority rule, since independent candidate Ross Perot siphoned off enough of the vote from both the Republican and Democratic parties to permit a Clinton electoral landslide even though 57% of Americans voted against him. Although the two-party system may be “broken”—Congress is stuck in a vicious cycle of gridlock and broken promises—the issue is not about creating an alternative party, but rather about dismantling the hegemony of the one-party two-party norm by adopting an alternative voting system altogether.

If disenchanted voters truly desire change in any form, IRV would deliver. The first and most important advantage of the IRV system is apparent: It eliminates the spoiler effect. Under an IRV system, the need for strategic voting would not be eliminated completely, but voters would not have to fear that they are countering their own interests when they vote for their first-choice candidate. A dedicated member of the Libertarian movement could vote Libertarian and then either Democrat or Republican, depending on his or her personal political beliefs. Because IRV diminishes the need to vote strategically, it would allow for third parties to finally garner the support that some voters have been too afraid to give them. In the rare but possible case of another election like 2000, voters—instead of Supreme Court justices—would be able to decide a contested presidential race.

Opponents of IRV claim that the system violates the principle of “one person, one vote,” as it ostensibly “gives minority candidate voters two votes” (a complaint voices by voters in Ann Arbor, Michigan when IRV was controversially used to determine the mayoral race there in 1975)—a second chance to prevent the most popular candidate from winning. But voters for the most popular party can be equally influential with their ballot by voting “against” all of the other candidates running, and simply not ranking them at all. In this way, they are declaring that they would prefer the election be “undecided” rather than risk having any of the other candidates elected. Even if their first choice candidate were to lose, as long as these voters are in the majority they can force another election by denying the other candidates the necessary majority to win.

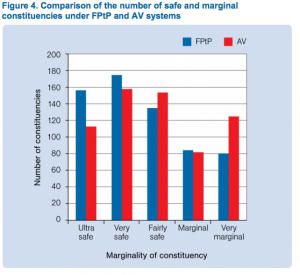

In fact, it is actually under the current system of FPTP that some votes are “more equal than others”—that is, one voter’s sway in a contested district is greater than that of a voter who lives in a solidly “red” or “blue” area. IRV has already proven to do better: a 2011 report by the New Economics Foundation on elections in the UK concluded that under IRV each individual vote mattered more and that the difference in individual voter power between districts was significantly reduced because there were more contested elections in SMDs.

Others complain that IRV and FPTP produce different results, meaning that the candidate who seems to be the clear frontrunner can be denied a decisive victory. For example, in the Irish presidential election of 1990, the candidate who had the most votes (43.8%) in the first round ended up losing in the second round, after minor party candidates’ votes were reallocated. But this is not necessarily a disadvantage: Who would want an electoral system that not only permits but also encourages minority rule?

Moreover, IRV makes it easier to overcome the incumbency advantage. A 2010 study from the Royal Statistical Society showed that under IRV, there was a much higher likelihood that members could lose their seats in elections, which increased responsiveness to possible citizen dissatisfaction. Thus, IRV makes “kicking the rascals out” of power more feasible.

Whether Americans find truth in Gore Vidal’s assessment of the “one-party system” in the United States or they simply feel that the current parties should have more of an incentive to deliver on their promises to constituents, an IRV system would provide solutions to today’s moribund political climate. It would create a system in which elections would be fairer, citizens would have more voting power and politicians would be less complacent.

Despite the headache of having to vote twice in the recent student elections, the benefits of the IRV system adopted by UCS certainly outweigh any negatives. By employing an IRV system, UCS is showing the world that it is committed to being more democratic than the national status quo. Let us hope that more institutions will follow Brown’s example.

**Todd Harris ‘14.5 is Chief-of-Staff at BPR