I’ll start with the low-down: there’s a good chance many in the political arena don’t fully understand the Three-Fifths Clause. And when Americans try to talk about the “horrors” of Three-Fifths, they may actually perpetuate serious sub-textual racism. And with that, I offer: SCANDAL OF THE WEEK!

Reflecting on the real purpose of Black History Month, Neil Singh wrote last week that “The bottom line is that most adults never learn the truth” about historical legacy of African Americans. He couldn’t be more right—the phenomenon is happening right now in Georgia.

Here’s the scandal. Emory President James Wagner wrote last month in the Emory Alumni Magazine that Congress should get its act together and compromise. Not exactly creative fodder for a great written article, but hey, innocent enough. Congress is so inept, Wagner argues, that they should look to the great compromises of our Founding era that cobbled the country together—and names, as his main feature example, the Three-Fifths Clause: the Constitutional declaration that a slave would count for three-fifths of a person in the representation of American citizens.

“Hmmm,” you may be thinking. ‘That sounds unbelievably dumb and flat out racist.” That’s more or less the sentiment at Emory’s campus, where a historical exhibition was coincidentally being held by the SCLC that same week. Nice.

But then he said something really, really racist: Apologizing the following week in a public letter, Wagner wrote, “Of course it is not good to count one human being as three fifths of another or, more egregiously, as not human at all, but property.”

Why is that racist? To answer that, it’s important to overview what the Three-Fifths Clause actually did in a basic way—an actual, honest breakdown, and not the Middle School version almost all of us (and clearly President Wagner) learned.

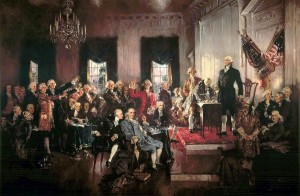

(by Howard Christy)

Here’s what the Three-Fifths Clause did: Because the Framers agreed that every ten years the House of Representatives should be reapportioned based on the Census, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 faced a serious problem—how to count the slaves in that reapportionment. This was the ultimate showdown between the early abolitionists and the Slave Power South—with abolitionists arguing that slaves should be counted as less of a person, and slave-owners arguing slaves should be counted as a full person. Abolitionists, not slave owners, wanted a two-fifths, one-fifths or—best of all—zero-fifths Clause; they wanted to “devalue” the humanity of slaves, according to the Middle School version. But why?

Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Garry Wills devotes part of his recent book, “Negro President,” to answering that question by tracing the legacy of the Three-Fifths Clause to the modern misunderstanding of the text Americans suffer today.

The answer? The higher the fraction of slave “representation”—whether three-fifths, four-fifths, or five-fifths—the more representatives the Slave Power South would gain. This is why Southern representatives of the Slave Power almost invariably controlled the most influential House Committees in the decades up until the Civil War, including the chairmanship of the Ways and Means Committee (then the most powerful committee) for forty-two years before the Civil War, and the Speaker’s office for forty-one, according to Wills.

But the plot thickens when we consider all the other advantages of the Three-Fifths ratio and the synthetic majority it gave to the Slave Power—and that list is unbelievably, mind-numbingly long. According to Wills:

“Without the federal ratio as the deciding factor in House votes, slavery would have been excluded from Missouri…Jackson’s Indian removal policy would have failed…the 1840 gag rule would not have been imposed…the Wilmot Proviso would have banned slavery in territories won from Mexico…the Kansas-Nebraska Bill would have failed.” (Wills, 6)

Finally, Wills points out the obvious: because of our system of popular sovereignty, the Three-Fifths Clause became the perfect vehicle to help the Slave Power metastasize throughout the various branches of government. The more Southern representatives, the more electoral votes; the more electoral votes, the more influence on the Presidency. And the more Slave Presidents, the more Slave Justices. In the sixty-two years before the Civil War, slaveholding Presidents accounted for fifty years, and eighteen of the thirty-one justices were also slaveholders.

The Three-Fifths Clause thus “gave the South a permanent head start for all its political activities,” writes Wills. A two-fifths, one-fifth, or better yet, zero-fifths clause would have erased much if not all of this legacy.

How does President Wagner fit into this? What is despicably racist is not that slaves were counted as three-fifths of a person—horrible as that is—but the fact that they were being “represented” at all, by a delegation that sought only to perpetuate their life in chains. When we yield to the Middle School version—and refuse to stare in the face the far more dehumanizing effects of Three-Fifths—I believe we arrogantly dismiss the truth to which an entire ancestral generation of chained Americans are entitled.

We need to fundamentally rework our understanding of what’s actually racist. The Middle School narrative of “just how awful” it was to treat someone as three-fifths of a person—thus implying that five-fifths would have been better, and unwittingly making the pro-slavery argument—does exactly what Neil fears: proscribes in its very premise the possibility of any serious exploration into our own past as a country and a people.